Back in high school, I knew boys who were handsome. Some of them even qualified as pretty. There was something special about a ranch boy with calloused hands and enviably long eyelashes. All those small town boys had been trained to be publicly polite. Most of them were privately polite, too. Even chivalrous. They were pale knights doffing their cowboy hats as they knelt in the wheatfields. Sir Tractor Wheel. Sir Rifle Rack. Sir Hay Loft. Those boys claimed I looked like Molly Ringwald, the beauty icon of our teen years, but that was just because of my red hair. If people wanted to exaggerate then I wanted to be compared to Ann-Margaret. I was only eighteen but I still believed in Bye Bye Birdie more than I believed in The Breakfast Club. I believed more in the movies of my father and mother’s beautiful youth. I believed in the stack of 1950s, 60s, and 70s VHS movies by our family television. I believed in what I was not.

There’s power in beauty. In Freeland, I got to choose because the boys thought I was beautiful. But they were flummoxed that I hadn’t chosen any of them. I didn’t think I was better than those boys. I didn’t feel beautiful. Has anybody ever felt beautiful? Even Molly Ringwald and Ann-Margaret? I didn’t need anybody to think I was beautiful. I certainly didn’t need anybody to flatter me. Or defer to me. I hope this doesn’t sound arrogant. Or condescending. I’ve always looked for things that other people couldn’t see. For things that I couldn’t see. I was always looking for whatever happened before the before and after the after. I was looking for a beauty that went far beyond any beauty that other people thought I possessed. I hope you understand. I didn’t think that I deserved the boys’ want. I just didn’t want their want.

My father, William, was the Lutheran pastor in our little farm town. Only 1,533 people lived in Freeland in 1986, but there were four churches: St. Jerome’s Catholic, First Presbyterian, Hillside Assembly of God, and Central Lutheran. There was another little church ten miles south of town. Most days, even Sundays, only three or four cars would be parked outside that church, which used to be a one-room schoolhouse. I didn’t know any Freelanders who worshipped at that strange place. It was called The Blessed Heart of the Lamb of Jesus, or something like that. It was hard to tell because their welcome sign was hand-painted, amateurish, and faded.

“Remember this once, remember it forever,” my father said. “Don’t trust a church with more than one prepositional phrase in its name.”

My high school friends were a multidenominational group so I’d gone to services in all four Freeland churches. The Presbyterians played the best music but danced like they were wrapped in rope. The Assemblers enforced the strictest behavior codes but prayed to God with the most jubilation. The Catholics were the most mystical but still obsessed over ordinary sins.

I’m not sure how to describe Freeland’s Lutheran Church. To define the church means I have to define my father. And who was my father? A deeply serious religious scholar who loved to mimic Charlie Chaplin’s duck-footed walk. A man who believed the Bible was error-free but needed my help with spelling as he wrote the church newsletter and his sermons. A man who believed that faith was the only way into Heaven but who enjoyed caper movies where the criminals escaped. A man who vacuumed his church three times a day but whose inconsistent hygiene left his nose hairs brambling out of his nostrils.

My father named me MartyJo, after Martin Luther, who started the whole Lutheran dance party, and after Joseph, who was not the biological father of Jesus, but still helped raise the Holy Spirit’s son. I was the girl forever connected to two Christian icons: the religious outlaw who hated the Pope and the beleaguered dude who was Jesus’s stepfather.

As you might guess, my father gave me a masculine name because he’d wanted a son who might follow him into the ministry. Instead, he received a daughter who preferred small-scale blasphemy. I wasn’t atheist or agnostic. I wasn’t the rebel daughter of a preacher man. I just thought the wrong lessons were being taught.

I was an only child because my mother killed herself before she had another. When I was three, she waded into Alder Lake with stones in her pockets and drowned. I barely recall being in her presence. In my memory, she’s a series of physical gestures and facial expressions. Freelanders regularly told me I looked like her and I saw the resemblance in family photos. Her red hair, her green eyes, her pale skin. But the real images of her weren’t as important to me as the glimpses of her in my mind. That was how I felt her love. That’s how I knew she’d loved me even as she submerged herself in Alder Lake. Sometimes, I sat on the hill above that lake and sang to her ghost. Sometimes, I heard my father weeping in his bedroom. I always found it amazing that my father, profoundly broken, kept testifying about God’s boundless love.

I often imagined that my father knelt on the carpet, clasped his hands, and wailed on my mother’s side of the bed.

Around midnight, on the night before our high school graduation, Ezekiel the Football Star stood below my second-floor bedroom window and tried to get my attention by turning his whispers into shouts and vice versa. He couldn’t have known which particular window was mine so he was speaking to all of them. He was trying to wake me without waking my father. I knew that Zeke could’ve thrown lightning and not roused my hibernating Dad, so I just laid in bed and pretended that I couldn’t hear Zeke’s whispered shouts. It was the first time that any boy had arrived like that. Zeke was my friend but his surprise visit was discourteous. Cocky. I’d never indicated that I wanted a midnight caller, especially a boy like Zeke. He was far too beloved by our little community. He was bulletproof.

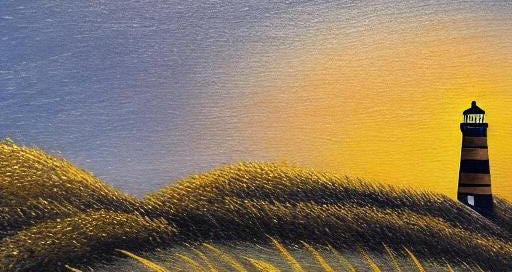

My father and I lived in a small house in the middle of a wheatfield five miles outside of Freeland. Our place had once belonged to the farmer who’d owned and worked the surrounding land. But that was decades ago. The house didn’t really belong to anybody anymore. I don’t recall if my father had ever paid rent or mortgage.

Our little home was so isolated that it was like an inland lighthouse. At night, our porch light must’ve looked like a small beacon. But a beacon isn’t a beacon unless its call is answered. And there was Zeke sailing in from the dark.

“MartyJo,” he said from below my window. “MartyJo, I’m not leaving until you talk to me.”

That sounded like a threat. And it pissed me off. So I climbed out of bed, turned on my desk lamp, opened my window, and looked down at him.

Ezekiel the Brave and Invasive.

“Hey, Feedbag,” I said. “What the hell are you doing here?”

He was wearing a John Deere baseball cap, denim overalls, and work boots. Trying to look like the farm boy that he’d never be. He was a townie. His parents owned the grocery store.

“I came here to say goodbye,” he said.

“We’re graduating tomorrow, Dipstick,” I said. “You’re gonna see me all day.”

“But I’m gonna see you in a crowd tomorrow. I want to see you alone tonight.”

“Are you drunk?” I asked.

“I’m sober as the Bible,” he said.

That didn’t make any sense. The Bible is filled with booze and a multitude of other mood-altering food and drink. Zeke was trying to woo me with an unbeliever’s wordplay.

Zeke the Secular and Clueless.

“You’re not impressing me,” I said. “And you aren’t getting into my room or my underwear.”

“Wow,” he said. “That was blunt.”

“Blunt as the Bible,” I said, echoing Zeke’s inanity.

“I didn’t come here to get in your pants,” he said.

“Then why are you here?”

“I don’t know. It just seemed like the right thing to do.”

“How’d you get here?” I asked. I knew that he didn’t have a drivers license.

“I walked,” he said.

“All the way from town?”

“Yeah, all the way. For you.”

“You’re my hero,” I said. “You’ve won my heart and loins.”

“MartyJo, you can mock me all you want,” he said. “It still sounds like birdsong to me.”

“Those aren’t birds,” I said. “They’re bats.”

“MartyJo, I’m gonna love you forever.”

I’d assumed that a few boys would declare their undying love for me during graduation week. And maybe a girl would confess her love for me, too. It wasn’t unusual. It wasn’t special. It was just the month of June, and all across the United States, high school graduates were declaring their eternal love to one or more classmates. But it wasn’t about romantic love. It was about kids who were already lonely for their childhoods.

“You don’t love me, Zeke,” I said. “You’re just afraid of the future.”

“I’m going to college,” he said.

“I know. You’re gonna play football.”

“No, I’m not. I’m not good enough to keep playing. No more football for me.”

I saw a few tears, illuminated by moonlight, roll down his face. Over the years, I’d seen dozens of Freeland High School seniors, boys and girls, mourn like that. They were at the end of their athletic careers. They’d never again play in a game that truly mattered. That small town grief was larger than almost any other grief in Freeland.

“But you’re not going to college, are you?” he asked, trying to sidestep his sadness.

“No, I’m not,” I said.

“Why not?” he asked.

“I’ve got reasons,” I said.

“What reasons?

“The reasons belong to me,” I said. “Not to you or anybody else.”

Zeke bowed, looked up at me, and said, “I understand, Juliet, you up there at your sad heights.”

Zeke the Poetic and Goofy.

“Okay, Romeo,” I said. “You paid some attention in English class. Now my loins are a bonfire.”

“Mock, mock, mock me all night long,” he said. “It will always sound like a sonata to me.”

“What are you doing here anyway, Beethoven?” I asked. “You should be celebrating with Ben and the others.”

Zeke. Ben. Doug. Tom. Ricky. We’d nicknamed them the Gold Dust Gang. The boys who would and could and did win everything. They’d always loved their moniker. Who doesn’t want to be golden?

“Ben and I are gonna celebrate tomorrow,” Zeke said. “Tomorrow night, the Gold Dust Gang will ride for the last time. Ben’s got a new grain truck. He keeps talking about rear axle weight or something. Who cares? Tomorrow is tomorrow. Tonight is only about you, MartyJo.”

“That’s a sweet thing to say,” I said. “But it’s a sweet thing wrapped in bullshit.”

Zeke laughed. I laughed.

“Come down here, please,” he said. “Please two-step with me.”

“That’s not gonna happen,” I said.

“Then I’ll have to dance by myself,” he said. “I’ll have to dance for you instead of with you.”

And so Ezekiel the Strong and Rhythmless whirled for me.

He held his arms out as if he were holding me and spun in clumsy circles. He kicked up early summer dust. He danced for a few minutes, dipped and kissed the imaginary me, and gently pulled her back to her feet.

Then, smiling, he tipped his John Deere baseball cap up to my window, at the real me, and walked into the real dark.

What does it mean to be a motherless daughter?

One would assume that I’ve spent my life searching for maternal figures. And that would be true. I was eleven when I first discovered Mary the Virgin Mother. Of course, I’d heard her name at home and in church constantly, but she was always a distant figure to me. I thought about Mary in the same way I thought about my mother. Both of them were shadows I loved. But then one day I heard, truly heard, my father tell his congregation that Mary is the Mother of God. And that illuminated the world for me. It wasn’t about being “saved.” I never believed in the concept of being saved because it always seemed that humans, and not God, were doing the picking and choosing.

Mary became my most trusted vision. I prayed to her far more often than I prayed to Christ or God or the Holy Spirit. In the absence of my mother, Mary became my ultimate mother. And as much as I resembled my mother, I also longed to resemble Mary.

In sixth grade, I changed my name from MartyJo to MaryJo and signed that on every essay, drawing, and test. My teacher tried to correct my spelling but I resisted. She tried to bring my father into it but he shrugged and said, “She’s my daughter, and I love her, and I think she’s on her own path.” After a few months of that, I changed my mind. I no longer felt that I was honoring Mary by naming myself after her. I didn’t want to share a name with the Mother of God. I didn’t think I deserved it.

I was just a child. I was smart, yes, but I didn’t know much about the sacred. I knew how babies were made but I couldn’t imagine making a baby. When I saw pregnant women in Freeland, I fled in the opposite direction. Conception was a miracle that I couldn’t bear. And what about the conception of the entire universe? Who but women carried and birthed life? In the natural world, many animals, insects, and plants have given virgin birth. A female shark in an Australian aquarium gave virgin birth to three babies, even though she hadn’t shared water with a male shark in years. And if a female shark can give virgin birth then why couldn’t a female human? And if Mary was the virgin creator of God then she must have been the virgin creator of the universe. The logic, illogic, fallacy, magic, irreality, mysticism, faith, doubt, and mother-ness were interwoven in my mind. They’re still interwoven in my mind.

Maybe Mary was more than the Mother of God. Maybe Mary was God.

And what of Jesus? I knew that I was supposed to feel his righteousness in my heart. But when I thought about Jesus, I could only feel my mother in my heart.

I wondered if I had somehow turned my mother into Jesus. I wasn’t prideful enough to believe that my mother was Jesus to everybody. She was my Jesus. And that greatly troubled me because Jesus of Nazareth walked on water. My mother didn’t walk on water. She drowned.

What does it mean to be a motherless daughter?

It feels like being alone in a church where a thousand women were scheduled to gather but never arrived.

At my high school graduation, I didn’t give the valedictorian or salutatorian speech. Those two genius kids had packed their suitcases in Kindergarten and had been waiting to escape Freeland ever since. I’d never been interested in striving enough for A’s so I worked hard enough for B’s. I thought my classmates might choose me to give the Most Popular Kid in Our Little World speech, but they chose Ben, who was the captain of everything and the only child of the richest farmer in Freeland.

I don’t remember anything specific from those speeches. But I’m fairly certain the smart kids talked about the future and Ben talked about the past.

Ben the Sedated and Complacent.

After the ceremony was over, the unpopular kids went their way, separately and together, and the popular kids planned to get drunk in various locales before finishing the night in one place. I didn’t go to parties. And I certainly didn’t drink. But my best friend, Liz, begged me. She was a black-haired girl with blue eyes. She played Snow White in a middle-school play and nobody let her forget it. We called her Snowy. She was heading to the University of Washington to be an engineer. She would eventually go to work for the City of Seattle and spend years trying to repair their bridges. We talked on the phone a few times over the years. She always said that the bridges in the whole damn country, not just in Seattle, were going to eventually collapse because nobody, not one American in charge, could get their shit together. I don’t think she was exaggerating.

Six months after Snowy went to college, her parents left Freeland and moved to a log cabin on the Montana-Canadian border. They thought Freeland had changed too much. That’s how a small town like Freeland begins to die. People wanting bigger or smaller things.

“MartyJo,” Snowy said. “It’s the end of high school. It’s never gonna be like this again.”

“Good,” I said. “Why don’t we just drive up to Spokane and eat some pancakes? We’ll grab some of the other girls and we’ll talk.”

“All you ever wanna do is talk,” Snowy said.

“I’m a good talker,” I said. “And a better listener.”

“I know, I know, that’s why I love you. But tonight isn’t about talking. It’s about celebrating.”

“You go ahead, Snowy. Have fun.”

“What are you gonna do?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “Go home and watch movies, I guess.”

“With your dad?”

“Yeah.”

“You’re such a daddy’s girl.”

Snowy was right. I spent a lot of time with my father, a lot more than a typical daughter, I guess. But he and I were the only people in Freeland who’d lost somebody to suicide. Over the years, various Freelanders had often tried to comfort my father and I, separately and together, by telling us they’d never heard of anybody else who’d committed suicide in Freeland. Not in all the decades. Maybe not since the town was founded. I guess they wanted us to believe our mother was inherently special because she’d died in such an unusual way. And there were some Freelanders who believed my mother was in Hell because she’d committed suicide. Some of them tried to hide their disgust. But I knew who they were. They looked at me like I was going to Hell because my mother had killed herself. Like Satan chose his tenants by lineage instead of by the sins they’d committed.

I never believed in Hell, not even when I was little. And neither did my father, not before or after my mother walked into the lake. And, as I grew older, I became less and less confident about Heaven. Never trust a person who says they know about Heaven.

Fifteen years after my mother’s death, I still couldn’t talk about it with anybody else except my father. Sometimes, we sat at the dining table and prayed together for her. Sometimes, those prayers made us feel better. Sometimes, we just sat in front of the TV and watched her favorite movies. She loved The African Queen.

Katherine Hepburn, the powerful redhead.

“She asked every time we watched it,” my father said every time that he and I watched the movie. “She always said, ‘Nobody in real life called him Humphrey, right? They had to call him something shorter, right? So did they call him ‘Humph’ or “Hump’ or “Ree” or what else? You gotta give a nickname to a man called Humphrey.’”

During my high school graduation ceremony, my father had leaned against the back wall of the gym with the other men who didn’t want to be too close to all that messy emotion. My father wasn’t afraid of emotions. He just wanted to silently support the men who were afraid.

“Come on, MartyJo,” Snowy said. “Let’s go make some memories.”

“You just wanna go find some boys,” I said.

“And what’s wrong with that?”

“Nothing’s wrong with it, Snowy. Don’t get pregnant.”

“You shut that mouth,” she said. She laughed and playfully punched me in the shoulder. It hurt a little. So maybe it wasn’t so playful. In October of our junior year, she’d pulled me into a bathroom stall. Crying, she hugged me and said that she’d finally got her period, almost one month late.

But there she was, unpregnant, on our last serious day together.

“Look over there,” I said.

Zeke, Ben, Doug, Tom, and Ricky, the Gold Dust Gang, were gathered around a new grain truck. Only Ben’s father could have afforded it. But Ben strutted around it like he’d bought it with a twenty-dollar bill and his even-teeth grin.

Ben the Armored and Vain.

“I hope they don’t drink and drive,” I said.

“I think that’s exactly what they’re going to do,” Snowy said.

“I hope you don’t end up marrying a boy like them,” I said.

“Never,” she said.

And she didn’t.

In 1999, on the 30th anniversary of my mother’s suicide, I found and swallowed every pill in our house and drank a bottle of wine. My father was supposed to be gone for the weekend for a Lutheran conference in Spokane. But he felt increasingly nauseous as he socialized with the other Lutherans so he packed up his things, checked out of the hotel, drove back home, and discovered me.

I won’t argue with you if you want to call it a miracle.

“How long do I have to stay here?” I asked the nurse. She was wearing a floral top and white pants. Basketball shoes. That was cute. Her nametag said Life & Light Treatment Center, which made it sound like a cult. The place seemed clean and well-organized. I doubted Nurse Ratched was going to come around the corner and lobotomize me like she did to Jack Nicholson in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. And I doubted that a giant Indian friend was going to mercy-suffocate my brain-fried nothingness with a pillow. I imagined Zeke the Somewhat Indian standing at my bedside with a distraught look on his face and a pillow in hands. I laughed. Sweet, sweet Zeke. He was incapable of hurting anybody like that, even as an act of existential love. He was an Orc on the football field but he was a Hobbit in his soul. I laughed again. My thoughts were scattered. Movies were rushing through my head. I laughed for a third time and then wondered if laughter was a sign of insanity. What happens to the person who keeps laughing in a mental healthcare facility? After all, the nurse was serious. I wondered if she’d ever laughed, Her name was Etta.

“You’ll stay here in the observation rooms for a few days,” she said. “And then we’ll move you into a cabin.”

“By myself?” I asked. I hoped for a single room. As an only child, I’d never shared a bedroom. I was so uncomfortable during sleepovers at my friends’ houses that I often stayed awake all night.

“You’ll have your own room here in observation,” Etta said. “You’ll have roommates when you move into a cabin.”

“Why are you observing me?” I asked,

“You’re here for your own safety,” she said.

“You guys think I’m gonna kill myself, don’t you?”

“You’re here for your own safety,” she said again.

We were standing in a little room. Maybe twelve feet by eight feet. A twin-sized bed. A night table. Primitive. One window. I wondered what would happen if I punched through the glass. What could I do with the broken shards? I thought of Bible camp. About the single rooms where senior camp counselors slept alone. Where I slept alone after long and wonderful days. I knew that I wasn’t at summer camp, but when I looked out that observation room window, I saw little Christian kids running through the dark with Fourth of July sparklers.

MartyJo the Dark and Hallucinating.

“This isn’t a summer camp, is it?” I asked.

“No, it’s not,” Etta said.

“It looks like a summer camp.”

“It used to be a Boy Scout camp,” she said.

“Do you guys give merit badges for craziness?”

“Please change into these pajamas,” Etta said. “You can leave on your bra and underwear. Fold your own clothes and place them on the foot of the bed, please. I’ll give you some privacy.”

Etta slid open the curtain hanging in the doorway and stepped into the hallway. My room was directly across from what looked to be the little pharmacy. A few people stood in line. Waiting to get their crazy pills. They glanced at me. They wore street clothes. I guess they’d graduated from the observation rooms. I wondered how they’d accomplished that. Etta slid the curtain shut, giving me only a little bit of privacy, I could hear the other nurses and other patients talking. Mostly friendly banter. The crazies had been molified. I imagined Etta holding a chair and whip to fend us off. One woman was quietly arguing about the dosage change of one of her particular crazy pills. I couldn’t see through the curtain but light streamed in from the bottom, top, and sides. A limited definition of privacy. After all, I was under observation. I was almost exposed. I decided not to care. What did it matter if I were naked or near-naked in front of strangers? Crazy people wander around naked all the time, don’t they? I stripped off my shirt and jeans. Why did they let me keep my underwear and bra? I think I could’ve somehow used one or both articles of clothing to hang myself. I looked around the room. There were no hooks or edges, nothing that would allow me the leverage to hold a noose. What are the physics of suicide? I pulled on my pajama top and bottom, sat on the bed, and waited. I looked down at my bare feet. What had happened to my socks and shoes? There were a pair of simple slip-ons on the floor. No laces. That made sense. Laces would’ve been the easiest way to kill myself. My feet were cold so I pushed them into the shoes. They were a little too big. Were they new? Or had they been washed and handed down to me from some other crazy person who’d stayed in that observation room? How many crazy people had slept in the bed? Dozens, hundreds, thousands?

“Knock, knock,” Etta said because there was no door to knock on.

“Come in,” I said.

She stepped through the curtain holding a paper cup in each hand. Water in one and a pill in the other.

“What’s that?” I asked.

“Klonopin,” she said.

“What’s that supposed to do?”

“It’s an anti-anxiety medication,” she said.

“What makes you think I have anxiety?” I asked.

“When was the last time you slept?” she asked.

I thought about that. Sometimes, I slept for days. Sometimes, I was awake for days.

MartyJo the Lightning and the Mud.

“Do you know when you last slept?” the nurse asked.

“I don’t remember,” I said.

She looked at me with a practiced blank stare. No, not blank. The pre-set expression of empathy. Or maybe real empathy. It was almost 10 p.m. She was working the graveyard shift. Though they certainly didn’t call it the graveyard shift in a mental health treatment facility. Or maybe the staff made that joke in private. Repeated it over and over. The graveyard shift in the graveyard of shoelaces and broken glass. I thought again about punching through the window.

I took the Klonopin.

In 1986, three weeks after graduating from high school, I was hired to waitress at the Freeland Cafe. It was a job I would hold, off and on, for decades. It was a fairly easy job. There were only six tables. Four chairs at the bar. It was usually filled with hungry Freelanders, but everybody was patient and tipped well. Hardest part was waking at 5 a.m. to serve breakfast to the farmers. No matter the season, they always ate their eggs and bacon before dawn.

In late July, Ezekiel the Football Star and his parents came in for early dinner. They were the first customers of the evening. I hadn’t seen much of Ezekiel that summer. Probably embarrassed by his midnight dance show at my house. I knew he was heading to college in a few weeks. He’d never been a science or math guy so I thought he might become a sportswriter. He could stay connected to football that way. Pour all his love into the words.

Zeke’s mother was named Bella. Short and thin. She was a Slavic immigrant and spoke fluent English with an accent. She often sang while working in their grocery store. Some of the lyrics were in English but others were in a language that I didn’t recognize at all. She laughed all the time. Even when nothing seemed funny. Like she was seeing absurd things that we couldn’t. I called her “Bella” aloud but sometimes called her “Mom” in my head. I did that with older women. Sometimes, it felt as if I were placing all of them in a Museum of Motherhood.

Zeke’s father was named Raymond. He was Indian, I knew, but I didn’t know what tribe. The old farmers usually called him Chief so Ezekiel was Little Chief. Those were racist and affectionate nicknames. Some of the farmers said that Ray was a full-blood Indian warrior. But none of that seemed true. Our little white town was equidistant between two Indian reservations and Ray was like none of those Indians. I’m no expert but he didn’t feel Indian. His hair was light brown and his skin was like a hot tea with six pours of milk. He was mostly a white guy. You could see it. And he wasn’t a warrior at all. He was kind. A little bit formal. A little bit ostentatious. He called me Miss MartyJo. I liked it.

I have such vivid memories of the brief moments I spent with Bella and Ray. I saw them alive and I went to their funerals. That’s what life is. We go to the funerals of people we know. And then people go to our funerals. When we’re alive, most of us try not to hurt people.

“Miss MartyJo,” Ray said. “What’s the Special tonight?”

“Meatloaf and mashed potatoes,” I said. It had been the only Special for years. Who doesn’t love meatloaf and mashed potatoes? Why not serve it for a lifetime of dinners?

“I think I’m gonna have one of them Specials, Miss MartyJo. How does that sound, Bella, my dear bride?”

“Sounds deeeeeee-lish,” she said.

“Another Special for the love of my life,” Ray said.

“How about you, Zeke?” I asked.

He just nodded his head. He didn’t make eye contact.

“Wow, Zeke,” I said. “You don’t have to shout.”

Bella and Ray smiled at that dumb joke. Zeke didn’t.

“My little boy is sad-in-the-face,” Bella said and laughed. “I think some girl broke his heart.”

She messed his hair. He pushed her hand away, stood up, and walked out of the Cafe.

“Is Zeke okay?” I asked.

“He’s been like this for weeks,” Bella said. “He’s barely left the house. Doesn’t see his friends. Nothing.”

“I think he’s scared about going to college,” Ray said. “You know, little town to big city.”

I didn’t think of Spokane as a big college city but I knew Freeland was very small.

“All right,” I said. “I’m gonna put your order in and go find Zeke. Talk to him a little. Is that okay?”

Bella and Ray were happy to hear it.

MartyJo the Compassionate and Minimum-Waged.

I gave the order to Sheridan, the owner and cook.

“Hey, Shy-Shy,” I said. “I’m going on break.”

“You got ten minutes,” he said. “Dinner rush coming soon.”

He smiled. There hadn’t been a dinner rush since Nixon resigned from the Presidency. That was when Freeland Cafe had the biggest TV in town.

I untied my apron and draped it over one of the empty bar chairs and then I walked out to find Zeke. It didn’t take long. He was in the little town park just down the street. He was doing push-ups. I sat on the grass beside him.

“Hey, Zeke,” I said. “How’s it going?”

He kept doing push-ups.

“How’s the Gold Dust Gang?” I asked.

“Don’t know,” he said.

More push-ups.

“How’s Ben?”

“Don’t know.”

More push-ups.

“What does that mean?” I asked. “When did you see him last?”

“Morning after graduation,” Zeke said.

“That’s almost two months ago.”

More push-ups.

“Did you get in a fight with Ben?”

“No. Can you please leave me the fuck alone?”

“Don’t you cuss at me,” I said. “What’s wrong with you?”

“Leave me alone,” he said. “You don’t care. You’re just doing your girl scout shit.”

“That’s not fair,” I said.

He did a few more push-ups, then dropped to ground facefirst, and started crying. Sobbing, really.

“Zeke, Zeke, what is it? What’s wrong?”

I put my hand on his back. He rolled away from me. His face was smeared with dirt. He stared up at the sky and kept sobbing. I looked around to see if anybody was watching. I was embarrassed and ashamed of my embarrassment.

I put my hand on Zeke’s chest. He put his hands on my hand and pushed down, as if he were trying to push our hands into his chest. I wondered what it would be like to hold a real beating heart in my hand. I thought about heart surgeons. They touch real beating hearts every day. Such power, such tragedy. Such redemption.

“Zeke, that hurts,” I said.

He released my hand.

“I’m sorry, I’m sorry,” he said.

He stopped crying like a hailstorm suddenly ends.

“Zeke, what is it?” I asked. “Please. Tell me. I’m your friend.”

He sat up and wiped the tears and dirt from his face. He exhaled. I don’t think I’d seen a Freeland man ever cry in public, except at funerals or big sports wins or losses.

Zeke the Unusual and Vulnerable.

“It’s nothing,” he said.

“It’s gotta be something,” I said. “This is ripping you up. You gotta tell somebody. Talk to me. I’m here.”

In a rush, he told me about an Idaho State Trooper who’d stopped the Gold Dust Gang on the night of our high school graduation. Stopped them as they drove drunk on a highway. The Trooper had called Zeke an Indian mongrel. He hit Doug in the knee with a heavy flashlight. The Gold Dust Gang burrowed into the earth. The Trooper shined a flashlight in Zeke’s eyes. A powerful flashlight. The Trooper unholstered his gun and pressed it to Zeke’s chest. Zeke was forced to walk into the terrifying dark while the Trooper played with his pistol. Zeke said he kept expecting the bullet to enter his skull. He said something about truck keys flying through the night like a satellite, breaking orbit, and crashing into the dark dirt ocean. He said the Gold Dust Gang celebrated when the Trooper drove away.

“I love those guys,” Zeke said. “I think they would’ve died for me.”

“They love you, too,” I said.

He stood. I stood.

“When are you leaving for college?” I asked.

“Mid-August,” he said.

“Zeke,” I said. “You gotta see the Gold Dust Gang before then. You need to see Ben before you leave.”

“I can’t,” he said.

“It was horrible what happened to you,” I said. “To them, too. I think they need you. More than they’ve ever needed you. And you them.”

“I can’t,” he said. “I just can’t.”

“Why not?”

He closed his eyes and dropped his head. Shame. Defeat. Exhaustion.

“Because when I think about Ben,” he said. “When I think about the Gold Dusters, all I can see is that Trooper. In my brain, that Trooper has replaced everybody I know. Even Ben. I look at my parents and see him. I look at you and see him. It’s like that Trooper has become a mirror. Like he’s me. Like I’m him.”

In 1998, when I was 30, I began my first day as local pastor of the Freeland United Methodist Church. It was the first Methodist church in Freeland. A church that no Freelander had asked to be created. I’d done it on my own. I’d originally wanted to be a Lutheran pastor but my father already held that job and our town wasn’t big enough for two Lutheran flocks and shepherds.

My church was a narrow little house where the four rooms were lined up one behind the other like little kids waiting for recess. Nobody had lived there for ten or twelve years, maybe more, so the place was drunk with field mice and spiders. The Methodist Conference had given us enough money to pay plumbers and electricians to repair the guts, but my father and I had to do all of the necessary carpentry.

The front room was my chapel, the second room was the kitchen and dining area, the third was the bathroom, and the fourth was my bedroom.

So it became the Methodist Church built by Lutherans. Ecumenical from floorboards to roof. And I was the Methodist pastor who still worked as a waitress at the Freeland Cafe. Ecumenical from grill to the back booth. The farmers, as old-fashioned as they were, loved me as a waitress, as a lifetime Freelander, but were suspicious of me as a pastor.

“Man is supposed to have dominion over the world,” they’d say. “Man has dominion over his house. That’s what men are supposed to have. Dominion. Women are supposed to be something else.”

“You’re paraphrasing Acts 2:17,” I’d say.

“You trying to teach us about the Bible? We know the Word already,” they’d say.

“In the last days it will be, God declares,” I’d quote, “that I will pour out my Spirit on all flesh, and your sons and daughters will prophesy.”

“That just means that women can share the Word,” they'd say. “It doesn’t mean that women should be in charge of sharing the Word. It doesn’t say that women can lead the whole congregation.”

“Methodists believe otherwise.”

“Well, then, I’m happy I’m not a Methodist.”

“You’re always welcome in my church,” I’d say. “Always. Acts 2:17 also says that old men will dream dreams.”

“You’re funny, MartyJo, now can I please have another cup of black coffee.”

“I’ve been called to service,” I’d say. “I will serve.”

Theological humor went over big in the Freeland Cafe.

Two weeks before my first service, after my father had set the front door straight in the frame, we sat on the porch, and drank iced tea.

“This is brave of you,” my father said. “I’ve thought a time or two about opening my own church. But I don’t have that calling.”

“I don’t know what I’m doing,” I said.

“I’ve been pastoring for years and years,” my father said. “And I still don’t know what I’m doing. Have you been working on your first sermon?”

“Been thinking about it a lot.”

“And?” he asked.

“And I don’t know what to say. I don’t even know if anybody will show up. Not many Methodists in Freeland.”

“Not many yet,” my father said.

“Maybe I can steal some Lutherans from you,” I said.

And he said, “There’s some Lutherans I’d want you to steal.”

Wow wow wow. I was immediately hooked and am hungry for more! Clapping!

I'm hooked and want to know more about Marty Jo.