In February, 1991, at halftime of a high school basketball championship game, my big brother, Arnold, rose from the audience when his name was called and hit a half-court shot to win a new John Deere riding lawnmower. The crowd was ecstatic. My brother has always been a popular figure in the Eastern Washington high school basketball world, first as a player and then as a fan. So he was being cheered by his family and many friends. But he was also being cheered by strangers because they were delighted to see my charismatic and overtly emotional brother celebrate his win. He jumped up and down. He ran around the court. A dozen friends mobbed him.

I wasn’t there when he hit the shot. I didn’t learn about it until I saw the highlight later that night on the local TV news.

“Forget the lawnmower,” the sportscaster said. “Give that man a car.”

I telephoned my brother the next morning and asked him what he was going to do with the John Deere.

“Giving it to Dad,” he said.

Of course, he gave it to our father. Our family home sat on an acre of wild grass that required regular mowing. We had a manual push mower that took too much time and effort so that John Deere riding mower became a sacred machine for my father. It became a mobile church for him.

Then, after diabetes shadowed my father’s eyes and left him unable to safely drive a car, he also used the mower as transportation to the tribal trading post.

It’s reminiscent of the David Lynch movie, The Straight Story, where an elderly man, too impaired to renew his drivers license, motors his lawnmower across Iowa and Wisconsin to reach his estranged and terminally ill brother.

But my father’s lawnmower journeys weren’t nearly as epic. The trading post is less than a mile from our house and my father would buy Pepsi and Three Musketeers bars, bring them home, and share his bounty with us.

That’s a lovely story about my father and John Deere, right? A tale of luck, tenderness, and generosity with a measure of sadness about my father’s diabetes and his failure to take care of himself.

While writing this essay, I remembered that I’d written a poem about my father and his lawnmower. I searched my files and found it.

Sugar Town After diabetes shadowed my father’s vision and left him unable to drive a car, he’d pilot his riding lawnmower to the reservation trading post and buy Wonder Bread and generic maple syrup so he could make his slow suicide version of French toast.

My poem mixes fiction and non-fiction. I’m fairly certain that my father never made French toast from Wonder Bread and maple syrup. But I think those two ingredients are funnier and more dramatic and depressing than soda and chocolate bars. The poem’s narrative is more interesting, I believe, because I fictionalized some important details.

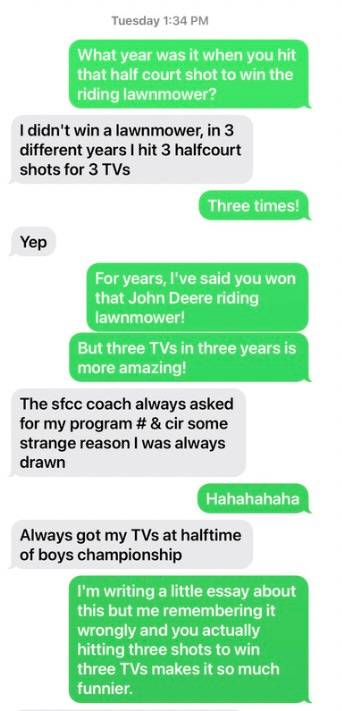

Then I wondered if I had also fictionalized details about how the John Deere riding lawnmower came into our lives. So I texted my brother to get his version of the story.

So, okay, after texting with my brother, after hearing his story that contradicted mine, I made some observations:

The basketball coach at SFCC (Spokane Falls Community College) obviously cheated when he pulled my brother’s name from the hat three different times. He just wanted my popular brother to win and thrill the crowd again and again and again. But my brother still needed the make the three half-court shots in order to win three TVs. It was a series of cheats that led to a series of chances.

I think the half-court shots are cool. In the movie in my mind, I can see three quick cuts as my brother hits those three shots—a sports movie montage. I haven’t mentioned that my brother’s weight, during his adult life, has always been in the 300 to 400 pound range. He doesn’t look like an athlete. He looks like somebody who could never do something as skilled as hitting three half-court shots in multiple years. But he has never lost his superior hand-eye coordination. My brother, no matter his weight, has always been a good athlete.

But I still think that my fiction about the diabetic-driven lawnmower is more interesting than my brother’s basketball stardom. Yeah, I’m the kind of poet who’ll mostly choose sadness over joy.

I kind of doubt that my brother hit three half-court shots. That just seems impossible. He must be fictionalizing his life, too.

Good for him. We’re storytelling brothers.

Does it matter that my brother and I have very different memories of his basketball halftime glory? Can’t both of our stories, however fictional, be true at the same time? It sounds like an oxymoron but good fiction must be true—or perhaps it’s better to say that good fiction must contain truth. Or Truth with a capital T if we want to go big about it.

I think of a letter that the poet John Keats wrote to his brothers in 1817:

…several things dovetailed in my mind, & at once it struck me, what quality went to form a Man of Achievement especially in Literature & which Shakespeare possessed so enormously—I mean Negative Capability, that is when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason…

I certainly don’t mean to place myself in the company of literary giants like Keats and Shakespeare. But, in my writing and in my life, I try to operate with Negative Capability. I try to accept uncertainty and Mysteries (with the capital M).

But I often fail. I wonder if I usually fail.

So, as I continued to ponder that John Deere lawnmower, I still believed that my version of the story was true—more true that my brother’s version. So I texted my sisters.

Sears? Sears? Is that what this comes down to? That my father purchased that legendary lawnmower at Sears? And, wow, I somehow turned that ordinary transaction into a half-court triumph? Can a lawnmower be a triumph? Or maybe “triumph” is the wrong word. Maybe I, the atheist Indian, should practice Negative Capability by quoting the Bible.

…because of the tender mercy of our God, by which the rising sun will come to us from heaven.

Luke 1:78

This is not a story of triumph. This is about God’s “tender mercy.” And I laugh at myself yet again because all of my poems are about God even if I don’t believe in God. And I think of the human capacity for tender mercy. And I realize that my fictionalized poem about my father might be a tender mercy. Maybe all of my poems about my father are tender mercies.

Tender Mercy Dear Father, I remember when your lawnmower broke down. I looked out the living room window and watched you turn the ignition key again and again but it just clicked and clicked. The engine ignored your efforts but you could not ignore our overgrown lawn. It needed to be cut. So you stepped off the riding lawnmower and pulled that old push mower from under the porch and wrestled that crude machine over the family acre and turned the wild grass into something almost tame. Then you looked up at the window and saw me, the child who shares your name. You lifted your open hands toward me and showed me the blisters on your fingers and palms. Dear Father, you died young of diabetes and alcoholism but I never doubted your love. No, that’s not true. Dear Father, I doubted you and I loved you and I wish you would’ve sobered up and lived another twenty years. But you didn’t. You chose an early death and I miss you, I say I miss you, I say it and I’ll keep saying it until I’m one of those elderly fathers who dies in his sleep and is (I hope) tenderly remembered and missed.

Share this post