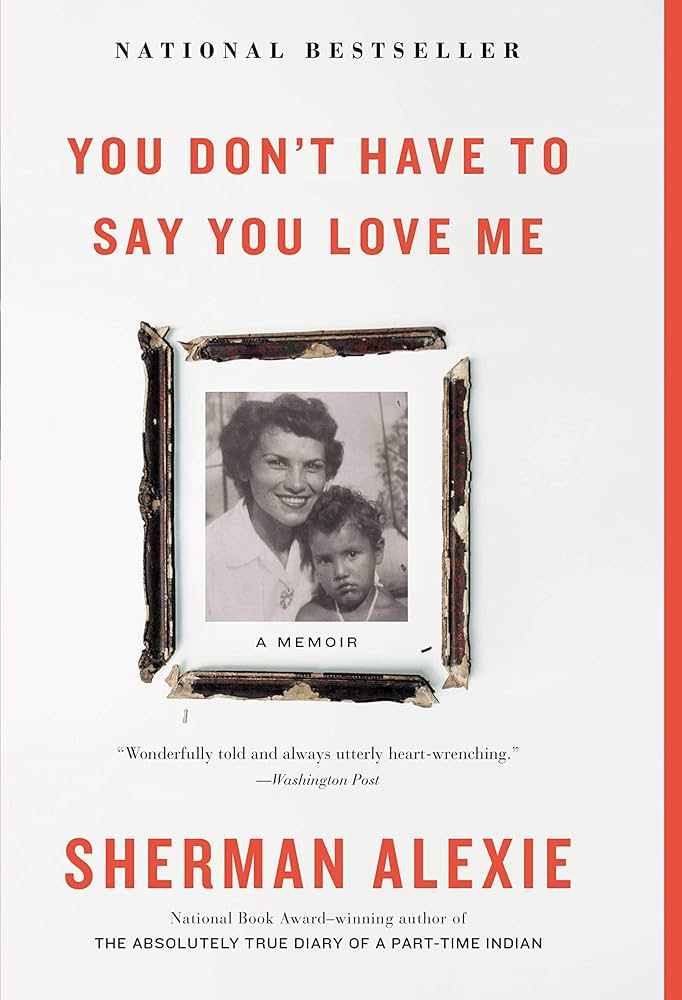

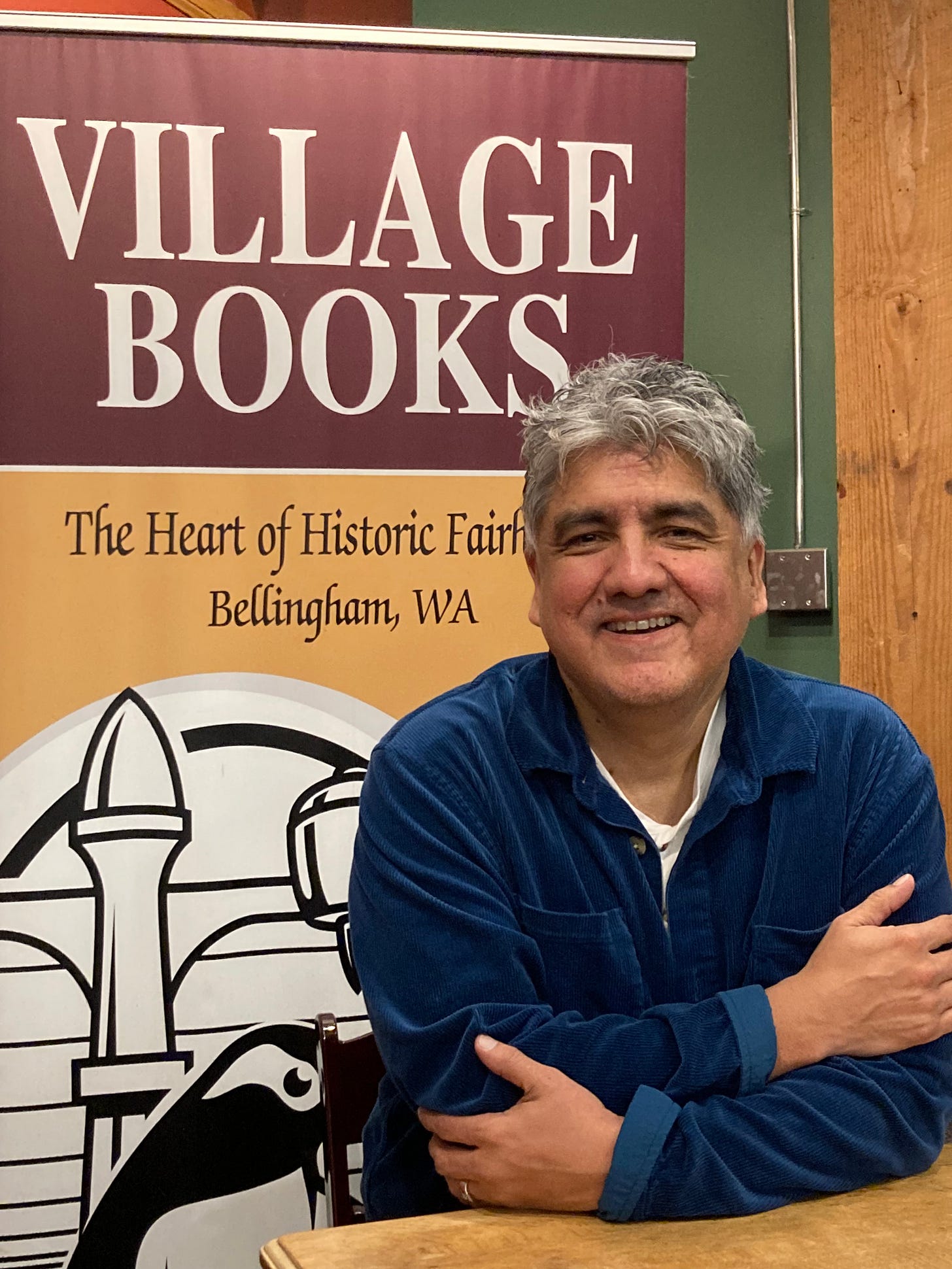

I’m still elated and exhausted from my two gigs in two nights at Village Books in Bellingham earlier this week. I had a great and painful time reading and performing You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me, my memoir about my difficult relationship with my mother.

That’s my late mother, Lillian, and late big sister, Mary, on the book cover.

A few of my college friends were in the audience at Village Books—including my freshman year roommate at Gonzaga University.

As I joked: “40% of my lifetime of roommates are here tonight. My wife, who’s been my roommate for 32 years, and Eric, my freshman year roommate. I had the other three roommates in two different residential mental healthcare facilities.”

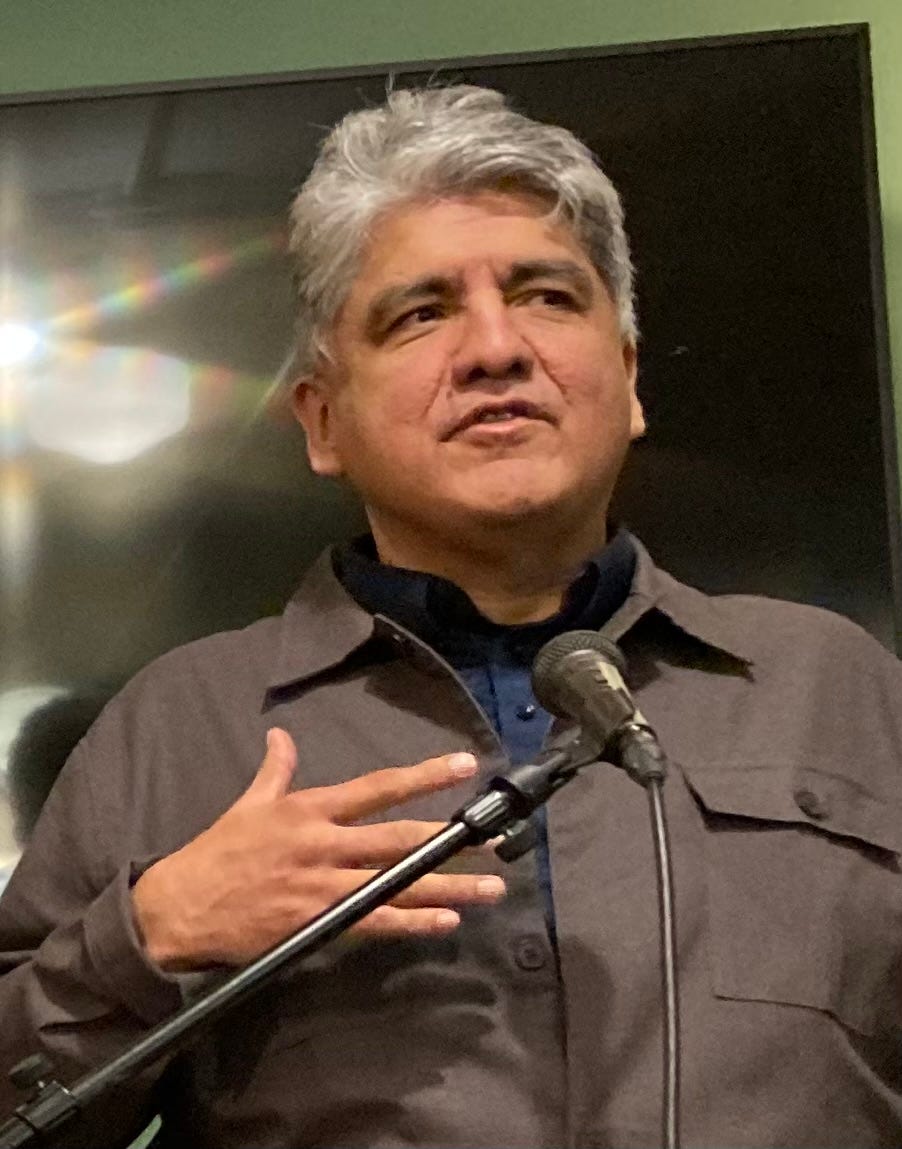

I’d done some small private gigs over the last few years but I hadn’t done a public event in a long while. I was nervous—a new feeling to me after three decades in publishing. I’ve long been a public performer. I played Santa Claus in a 4th grade stageplay on the reservation. Talk about a tough crowd! You don’t want teenage Indian boys giving you shit because your lisp has you calling yourself “Thanta Clauth.”

And, as I joked in Village Books, “You don’t wanna be the Indian boy with a lisp playing a wise man in the Nativity scene who has to keep saying, ‘The baby Jeth-thuth.’ That’s two S-sounds in one holy word.”

In 2017, while on book tour with my memoir, I emotionally and physically collapsed. I’d been diagnosed with bipolar disorder in 2010 and had publicly revealed that fact. But, like many people with bipolar disorder, I had a contentious relationship with medicine and therapy. So I was not at all prepared for the emotional toll of the book tour. Or of the very writing of the book itself. I was an untreated bipolar man and I wrecked myself on the reefs, hidden and not, inside my brain.

I believe that my mother lived and died with undiagnosed and untreated bipolar disorder.

As I’ve been learning to have more empathy for myself and my many faults, I’ve also been learning how to have more empathy for her—my dear mother.

Nearly eight years later, I’m in a far healthier place. My medicine shuts the door to the attic of mania and the door to the basement of depression. And my dialectic behavior therapy helps me keep those doors shut.

And I discovered in Village Books that I’m now strong enough to talk about my memoir without fear of collapse.

And I’m eternally grateful to Kelly and Paul, co-owners of Village Books, who hosted me. They’ve been my friends for a very long time. And I’m honored by their support.

And, oh yeah, you had to be there to hear my story about how Nacho Cheese and Cool Ranch Doritos play integral roles in the Grief Poop Ceremony.

It did my soul good to hear you in person again. Years ago, I went to see you at Town Hall in Seattle with high school students. Pedro, a senior who is now a principal in an elementary school, told people in the audience you were his dad. When I shared this with you, you signed his book with something like “to my son, Pedro.” He now has a three-year old son and I gave him a book you said was your favorite as a child, The Snowy Day, and signed it saying it was his grandfather Alexie’s favorite book. Another generation has found Sherman Alexie.

My alter ego, Queen Poopicina, says, “I simply must know more about the Grief Poop Ceremony. Now.” She’s a full-on sovereign colonizer, so…

I’m thrilled that your creative powers have aligned with modern meds to land in a place that feels balanced. And Okay. ❤️🩹 My mom passed in January. I’ve set down my lifelong project of healing her wounds and trauma. Still, Mama heart strings pull hard for a long time. Grateful for you, making music on those strings, and the hard labor of healing.