The "I" in BIPOC: Not All Native Americans are Leftist Political Activists

Essay

During my lifetime, there have been three phases when Native Americans and Native American culture suddenly became extraordinarily popular.

The first was in the early 1970s with the rise of the American Indian Movement (AIM), a radical Indian-led political group that fought for Native American civil rights and tribal sovereignty. AIM’s ambitions were vital and necessary, if not in lasting political accomplishment then with the development and nurturing of a still-present ethnic self-esteem. AIM is legendary. But AIM’s political activism was sometimes marred by violence, committed by and against its members. The pop culture nadir of this era occurred during the 1973 Academy Awards when Marlon Brando, in protest of the continuing government oppression of Natives, sent a faux-Native American, Sacheen Littlefeather née Mary Louise Cruz, in his place to accept his 1973 Best Actor Oscar. Rarely has a thespian’s award-ceremony political grandstanding been so self-serving.

The second phase of Native American popularity occurred in the early 1990s when the New Age religious movement turned Native spirituality into a capitalist fad. That was the heydey of the “plastic shaman,” when white gurus led white customers through very expensive and supposedly sacred and authentic Native American ceremonies. Some of these white gurus became multi-millionaires. Perhaps the most ridiculous remnant of this era is the continuing enshrinement of Sedona, Arizona, as a Disneyland of sacred vortexes, audio-guided vision quests, dreamcatchers, tarot cards, and a McDonald’s whose outdoor arches are so building-mandate short that one can easily drive past them and miss their chance to eat a harmonic Big Mac. And, yes, this phenomenon is silly but even years after its heyday, it can also be deadly.

A jury has convicted a self-help author who led a sweat lodge ceremony in Arizona that left three people dead.

Jurors in Camp Verde, Ariz., reached their verdict Wednesday after a four-month trial.

James Arthur Ray was found guilty of three counts of negligent homicide.

More than 50 people participated in the October 2009 sweat lodge that was meant to be the highlight of Ray's five-day "Spiritual Warrior" seminar near Sedona.

—Felicia Fonseca, NBC News, June 22, 2011

The third phase of Native American cultural popularity is happening right now. It began in 2016 with the Standing Rock protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline in South Dakota. Thousands of Natives and non-Natives traveled to the Standing Rock Reservation for a year-long occupation to specifically decry the pipeline in particular and to generally protest the exploitation of Native lands everywhere. It was an inspiring and unprecedented moment in Native history—truly magnificent—though it had its own share of pop culture silliness. Case in point: they slapped a cowboy hat on Jesse Jackson, put him on a horse, and paraded him through camp. I like to imagine that Jackson, while riding that horse, was transported back to his childhood and thought, I’m an Indian, I’m a cowboy, I’m a real Indian cowboy!

During this third wave of Native American popularity, we might have reached an all-time high when we became the “I” in BIPOC—when indigenous people were officially given our own letter in the Racial Acronym of Leftist Activism.

I’m indigenous. Yes, I’m a Native American. An Indian. An American Indian. More specifically, I’m an enrolled member of the Spokane Tribe of Indians and grew up in Wellpinit, Washington, on the Spokane Indian Reservation. I lived on my reservation full-time until I was 20 and part-time until I was 25. Three of my four siblings still live on our reservation. Our late mother was Spokane Indian and father was Coeur d’Alene. Seven of my great-grandparents were Indian. The eighth great-grandparent was half-Indian. I’m married to an Indian woman who is an enrolled member of her tribe, the Hidatsa of North Dakota. Both of her parents were Indians. Six of her eight great-grandparents were Indians. During her childhood, she lived on five different reservations. So, yes, I’m far more culturally, genetically, domestically, economically, politically, and geographically an Indian than at least 90% of the people who identify themselves as Indian.

While reading this essay, Indian critics will object, “You think you’re more Indian than me, don’t you?” And my answer will be, “It’s nearly certain that I am more Indian than you.”

I’m an Indian who grew up with two Indian parents and lived in an unfinished government-built house across the street from the tribal school. How more Indian could I be?

To give you some visual evidence, here are my late mother and father as teenagers:

I’m presenting this biographical (and arrogant) information in order to establish my expertise. There is such a thing as Indian expertise. As the saying goes, “I’ve been Indian since conception.” As the other saying goes, “I’m the Indian boy Edith Wharton who’ll teach you something about the social means and mores inside the indigenous world.”

And I’m also giving you my Indian bonafides because far too many official and unofficial public representatives of Indian-ness didn’t grow up in tribal communities or even in tribal families. There is a huge difference between acculturated and unacculturated Indians. So I want to make it clear that I’m an acculturated Indian.

As you may or may not know, I’ve committed a political sin by not capitalizing “indigenous.” That’s the preferred, even required, nomenclature currently used by many to describe that group of people more popularly known as Native Americans. I’m a rather leftist indigenous person, a so-called progressive with a few socialist impulses (though in this illiberal era, I’ve been daily moving more and more of my furniture into the Milan Kundera-ish House of Classical Liberalism) and I’m here to tell you that Indians don’t in commonplace refer to one another as indigenous.

In fact, the word “indigenous” has now become a generic term that is used to describe (and self-describe) any American who has any degree of biological connection to indigenous people anywhere in the world. In this way, a Samoan American is now grouped with Native Americans in cultural and political terms. An American with a Guamanian grandmother is now grouped with a Navajo or Lakota. In the United States. “indigenous” used to mean “Native American.” Now, it’s just a label that justifies the false belief that brown people worldwide should be grouped together because we were colonized by many of the same forces. So, yes, it’s hilarious to note that the word “indigenous” now seeks to finish colonialism’s ultimate mission: to disappear individual people and cultures into the mainstream population.

I’m also here to tell that this third wave of Native American mainstream popularity will likely fade just like the others have faded. We’ll stop being the Most Beloved Other and transition back into being the Tragic Afterthought. Though I do think this era might last a few years longer than usual because using the word “indigenous” seems to have an unprecedented amount of cultural and political power.

I keep telling Indian writers, artists, and filmmakers to finish their books, paintings, sculptures, and movies, and send them out into the world because the market is hot. There’s more profit to be had for Indians precisely because non-Indians are making more money and social cachet off Indian-ness than ever before.

And I write “non-Indians” instead of “white people” because, for the first time, a significant number of non-Indian People of Color are claiming to also be Indigenous, thus becoming the ultimate intersectional victims and victors. Substitute “Sedona, Arizona” for “any college campus” and you’ll have a clearer idea of what’s happening.

In reading this essay, you’ll notice that I use “Indian, “Native,” and “Native American” interchangeably. And that’s because, in the Indian world, they are interchangeable. I could also refer to us as “NDN,” “Inj,” and “Skins,” but those are self-names that you non-Indians should completely avoid.

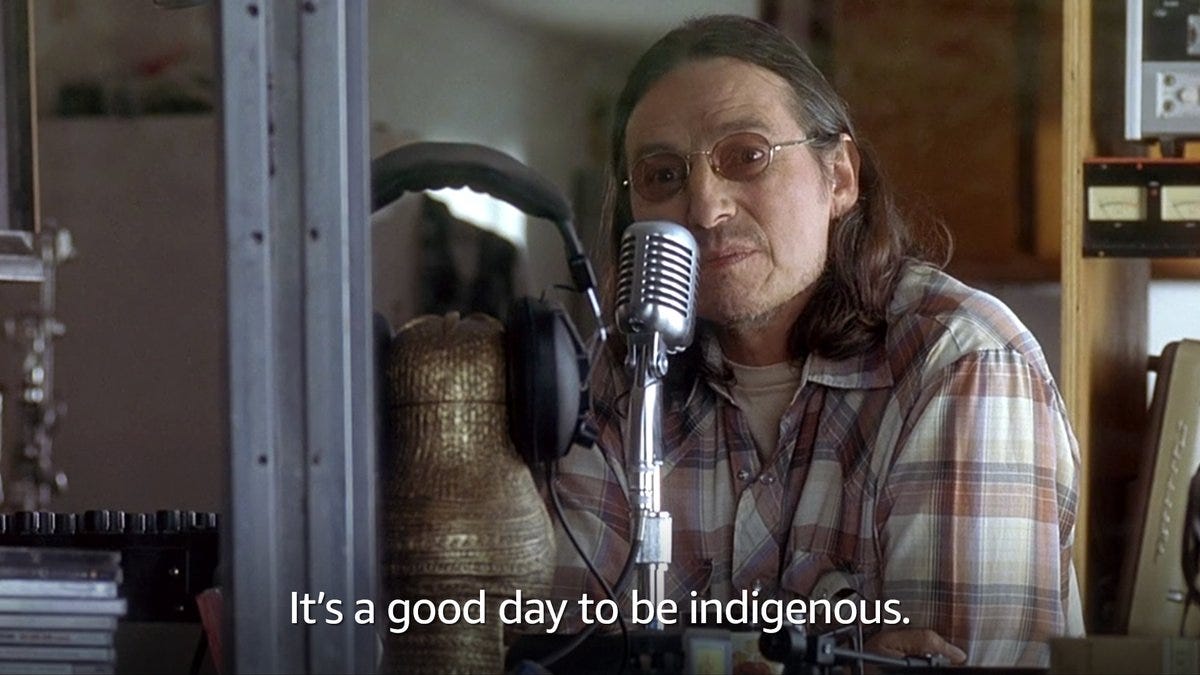

To be clear and contradictory, I’ve often used “indigenous” to describe Native Americans. One of the more famous and repeated lines of dialogue in Smoke Signals, the 1998 feature film I wrote and co-produced, is “It’s a good day to be indigenous.”

“It’s a good day to be indigenous” is a play on that fabled cross-cultural war cry, “It’s a good day to die.” My particular version of that phrase is the subject of many memes on the Indian Internet. Look it up now: “It’s a good day to be indigenous.” You’ll find it as a suggested search after you type the fifth or sixth word.

And I give you this bit of cinematic history to prove that “indigenous” is a word whose in-group history pre-dates its current popularity. I also place the word in a humorous context, then and now, because it’s a word that has only recently taken on such a relentless seriousness.

But it hasn’t turned into a pious word by the ordinary denizens of the Native world. No, it’s a word that’s now monopolized and canonized by leftist Indian political activists and their leftist non-Indian allies. I understand that the “I” in BIPOC is meant to convey pride and solidarity. And I agree with that mission. That mission is essential. But I think that “indigenous,” as politically employed, has instead become a word that restricts the meaning of what it is to be an Indian. I think it has created a national and international illusion that that only proper way to be an Indian, or to be an Indian at all, is to be an Indian who is a leftist political activist.

So allow me to make a statement that is simultaneously bold and banal: The Indian world is not filled with leftist political activists.

I’d argue that leftist political activists are only a small percentage of the Native demographic. I would posit that the basic Native political identity is ethnocentric, Democrat, capitalist, socially moderate, remarkably magnanimous, and only intermittently passionate. In other words, the Native American world is very…American.

This political disconnect between the very public leftist Indians and the more circumspect Native American population echoes throughout the BIPOC world. Based on various polls, it seems clear that leftist BIPOC activists hold many positions that are not widely shared by their own communities. The epic and aforementioned protest against the North Dakota Access Pipeline might lead you to think that was the result of a universal set of indigenous environmental philosophies. But there are many Indian tribes (including at least one upriver from Standing Rock) who have entered into lucrative deals with energy corporations.

And let’s not be romantic about the proliferation of Indian casinos. In pursuing our sovereign economic rights, Indian tribes are doing business with gambling mega-corporations that are not exactly models for leftist sustainability and socialist economics. Marx probably wouldn’t have kept a timeshare in Las Vegas (though he certainly would’ve fought for better working conditions for the casino workers). I’m an advocate for tribal sovereignty but Indian casinos make me queasy. And they make me queasy precisely because I’m a progressive who is wary of corporate power and its attendant cultivation and harvesting of human vice.

Many Indians view casinos as freedom. I see them as freedom and assimilation.

Of course, leftist Indians are going to strongly resist and perhaps condemn all of these observations. That’s okay. I welcome dissent. And I understand that, in order to defend their political and social identity, the Indian leftists must insist they are representative of the Indian world. That’s exactly how political subgroups operate. We need to enforce the belief that our individual or small group opinions are the national consensus.

It shouldn’t surprise anybody that Indians hold a diverse set of political beliefs. We are, ya know, human. But I still think this information will shock a whole lot of people. I doubt many people know that there are currently four people in the U.S. Congress who are members of Indian tribes.

Sharice Davids, Ho Chunk, is a U.S. Representative from Kansas and Mary Peltola, Yu’pik, is the U.S. Representative from Alaska. Both of them are Democrats. And both have been celebrated for being Indians in Congress.

But, as far as I can tell, the media world has zero clue about the two other Indians in Congress. And I’m sure their Indian identity is unknown, unacknowledged, and unexamined because they’re very conservative Republicans—Trump Republicans, in fact. Tom Cole is a U.S. Representative from Oklahoma. MarkWayne Mullin is a U.S. Senator, is also from Oklahoma. Mullin is Cherokee and Cole is Chickasaw.

Yep, some Indigenous people are right-wingers. I know this is not common knowledge. I would guess that even most leftist Indians don’t know there are Trumpian Indians in Congress.

I can predict what counterpoint the leftist Indians will offer in response to the Duet of Trumpist NDNs. The leftists will implicitly and tacitly argue that Cole and Mullin aren’t really Indian because they aren’t leftist or even just centrist. Or they’ll go after their physical appearance: Davids and Peltola have brown skin and dark hair but Mullin and Cole certainly look like typical white dudes (and they are indeed mostly white). But all four of them are recognized members of their tribes.

I’d bet that many non-Indians readers of this essay are now asking themselves how any Indian could be a right-winger. Well, I imagine the Trumpian duo of Mullin and Cole think of themselves as existing fully inside the powerful and ubiquitous tribal trope of Indian warriors battling against oppressive American institutions. Maybe those two exaggerating patriots look in the mirror and see Geronimo in a MAGA hat. After all, who has more reason to be contemptuous of the United States government than an Indian?

And here I must stress that Indians, whether conservative, centrist, or liberal, have a unique place in the United States that BIPOC doesn’t even begin to address. On a political and economic level, Indians share very little in common with Black people and other People of Color—with POC being a separate acronym that describes a vastly diverse population who likely take issue (but maintain a peer-pressured silence) with being lumped together as one. BIPOC is an acronym that’s too plain to accurately represent Indian people’s complex relationship with our country. Indian people belong to nations that interact, nation to nation, with the United States. In fact, Indian tribes already enjoy much of the economic, political, and cultural power that other POC are seeking to take, gain, earn, or deserve (the verb depends on your politics). Indian tribes are land-based and have (tenuous) control over vast resources. And they have constitutional rights that sometimes go beyond what even privileged Americans possess. Of course, we only have those rights because of the bureaucratic and atonement-driven aftermath of centuries of colonialism and genocide—with genocide being another word that’s subject to vastly different political definitions. I call it genocide. It certainly fits within the United Nation’s definition of genocide.

But let’s move on from genocide (which I have to stress for my unfunny readers is meant to be a Mel Brooksian sentence). I’m only a POC in the most generic sense. And I’m only indigenous in a general way. Calling myself indigenous is like calling myself an American. It lacks the specificity of personal and tribal identity. An Irish American from Seattle is not the same as a French American from Louisiana. A Russian American from Albuquerque is not the same as a Jewish American from Brooklyn. A Spokane Indian is not the same as a Hidatsa. A Navajo is not the same as a Mohawk.

And to pull out that Indian expert card, I’ll tell you that a reservation-connected Indian is not the same as a Indian who grew up in the city. We call them Urban Indians. Urbs, for short. And, yes, I’m now what you would call a rez-raised Urb. There are approximately 1.5 million Indians who are deeply reservation-based and/or reservation-connected, and some of us are deeply-connected Urbs. But of the approximately five million people who self-identify as being Indian, I’d say that far less than half of them have a specific connection to their claimed tribes. To be even more blunt, I’d say that an overwhelming percentage of the people who claim to have Indian ancestry have no connection to actual Indian ancestors or have such distant Indian ancestors that the connection was broken long ago. And I’d guess that only a tiny percentage of these self-imagined and disconnected Indians have even visited their claimed tribe’s reservation or home community, let alone formed any lasting personal relationships with members of their tribes.

So what to make of those leftist Indian activists—some real Indians and some not—who are disconnected from their own indigenous history? Those Indians often call themselves “de-tribalized.” As you may or may not know, there are people who really stretch the time frame of the de-tribalizing process. There are some who claim to be de-tribalized because of one Indian ancestor who died in the 19th Century or even earlier. There are entire tribes whose Indian identity is based on the connection to one distant ancestor. One of my 19th Century ancestors was a Scottish immigrant from Orkney who himself was possibly descended from a Viking named Thor (not that Thor). But I’m certainly not a Scottish American, let alone Scottish, though I like to complain that I’ve been de-Vikingized.

Here’s the thing: In the absence of a specific tribal connection, the de-tribalized Indian activist will find their indigenous identity almost completely inside their leftist politics. Instead of going to powwows, they go to protests. Instead of going to stick games, they go to organizing meetings. Instead of hanging around the campfire, they hang around Twitter. Instead of going to tribal ceremonies, they lead a theology-free life, or pursue astrology, Tarot cards, and other appealingly-pagan spiritual hobbies with the intensity and anti-science self-parody of any other type of religious zealot.

There are, of course, many tribally-connected leftist Indians. I love the Instagrams and Tik Toks of Indians fancy- and shawl-dancing for social justice. They’re beautiful.

But the de-tribalized Indian’s politics becomes their only expression of indigenous culture. In many ways, their politics and spirituality merge to become a fundamentalist religion. And it’s inside that fundamentalism—inside that indigenous orthodoxy—where the narrowing of identity can become dangerous. I’d venture that every war in human history is about the willful and enforced narrowing of human identity. And that process, at minimum, is certainly joyless.

Most troubling, the joyless and disconnected Indians, without ever having directly experienced the oppression that comes with being an Indian, often end up enjoying most of the benefits of being Indian—the cultural and political prestige and the jobs that are specifically meant to be for Indians.

Despite the current obsession with “lived experience,” there are leftist public figures who self-identify as Indians but have never experienced what it means to be surrounded on a daily basis by multiple generations of Natives. These leftists’ Indian identity is then defined by their distance from tribal culture. They become representatives of an un-culture, where their “lived experience” is almost entirely imagined. They present themselves as tragic victims of colonization without ever having faced any of the physical, emotional, spiritual, and cultural trauma that is endemic in Native communities.

Simply stated, urban elite progressive indigenous people have more political and cultural commonality with urban elite progressive white people than they do with the average reservation Indian—especially those Indians who are of older generations and tend to be more conservative.

Growing up on a reservation and being an Urban Indian adult who remains connected to his tribe and, yes, also consciously distant in certain ways, I’ve experienced the full range of Indian identities. And I’ve experienced so much joy in being an Indian among Indians. I don’t think the outside world knows that Indians are hilarious. Pretty much every tribally-connected Indian would kill at a comedy club open-mic night. Indian humor is so vital in Indian culture that I’m always suspicious of the unfunny Indians (and I’m actively scared of unfunny leftists in general). I’m suspicious of an Indian who doesn’t find it hilarious that some Indians love Trump. I have Indian friends and family who are Trumpites. And I have Indian family and friends who are Marxists. I have Indian family and friends who are spiritual leaders and followers inside of tribal traditions. I have Indian family and friends who are spiritual leaders and followers inside of Christian traditions. I have Indian friends and family who span the political, economic, and cultural spectrum.

And this spectrum of Indians easily live among one another. They practice their tribal cultures without much, if any, reference to political identity. There are no Indian Republicans or Democrats in the sweatlodge. There are only Indians. Politics have very little meaning in our most sacred places. We connected Indians don’t find the totality of our indigenous-ness in our politics. God, I can’t imagine how awful that would be. I’d be happy to sit beside the most Trumpian of Indians at a powwow and argue about which of the drum groups is the best.

I mean, hell, there are Indian Covid-deniers and anti-vaxxers. There are dozens of them in my tribe. Some of them are members of my family.

My “lived experience” as a reservation and urban Indian is kaleidoscopic. Yes, I carry the Kaleidoscope of Indigenity wherever I go. I inherited that Kaleidoscope from my late grandmother. She traded her “American Indians for Nixon” campaign button for it.

I love the glorious awful beautiful horrific wonderful disastrous miraculous oppressive free mess that is the United States.

Yes, I should've mentioned that a lot of Indian anti-vaxxers are indeeded motivated by the history of smallpox epidemics among Natives.