Sitting in the back row of the small art house theatre—only 6 rows of 8 seats—I glanced down at my ankle and noticed a scar. I was wearing sneakers with no-show socks. My wife and her sister call them “weenie socks” so I also call them “weenie socks” even as I’m wearing them. I studied the scar on my ankle. It was maybe an inch-long, maybe a little longer, and a bit ragged. My scars tend to keloid because I have more melanin in my skin. So the scar was raised and obvious.

I don’t know why I first looked down at my ankle. Maybe I was engaged in a subconscious investigation of my body and soul because I was waiting to see In a Lonely Place, a 1950 film noir that stars Humphrey Bogart as a troubled and violent war veteran and screenwriter who grapples with PTSD, Hollywood amorality, and homicide detectives who regard him as a prime suspect in a murder. I’m not a war veteran or suspected criminal, of course, and I’m not violent, but I’m certainly a mentally ill screenwriter with serious Indian reservation PTSD and far less serious Hollywood PTSD. So, yes, I knew Bogart’s portrayal of Dixon Steele (What a name!) would have autobiographical echoes for me. Like Steele, I have various physical and emotional scars but I realized in the theater that I had no memory of how I’d cut my ankle badly enough that it became a distinct if small scar.

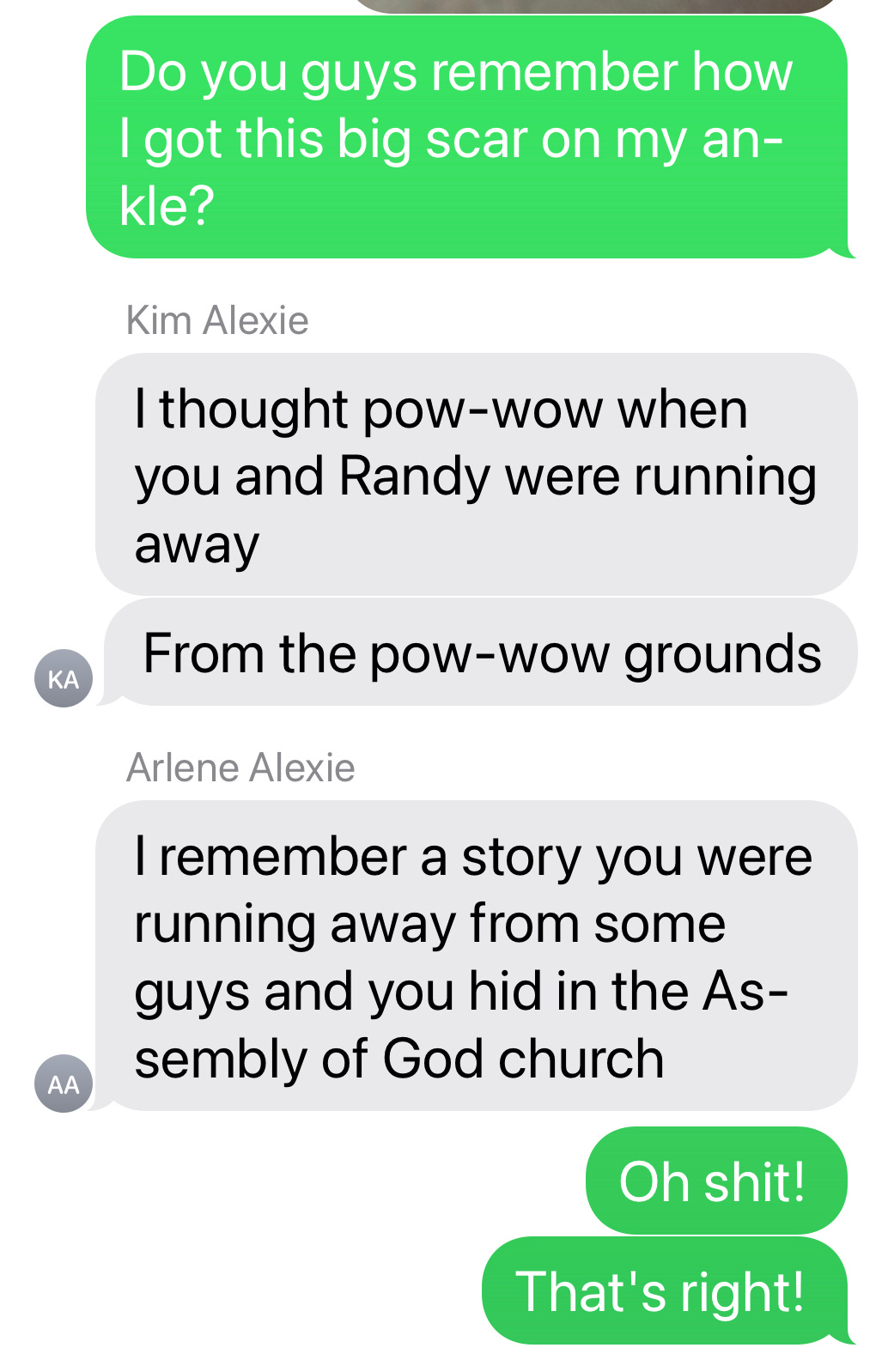

My little sisters usually have better memories of our childhood than I do. They’re identical twins, and only 358 days younger than me, so I like to pretend they have a shared and much larger database than I do. After I returned home from the movie, I texted them.

Randy was my best friend on the reservation. He was a short and pale Spokane Indian with a wicked temper. I don’t know why he was so quick to anger. His siblings were all peaceful kids. I was often bullied on the rez so Randy sometimes functioned as my bodyguard. He’d also punched me twice during arguments but only in the belly because he didn’t want to mess up my face.

But Randy was more than just a boy who liked to throw fists. I’ve always been an emotive person, quick to cry when I felt joy, sadness, or fear. It’s always been shameful and potentially dangerous to be a weepy American boy, and a weepy American man, but Randy never made fun of me. One night, in sixth grade, as I cried to him about my latest unrequited affections for an Indian girl, Randy sighed and said, “You fall in love too easy.” Yeah, he said that in sixth grade. And, yeah, he was right.

And, yeah, my sisters, the family archivists, had reminded me that Randy and I had gotten into trouble at our tribe’s powwow in 1979.

The Spokane Tribe’s annual powwow is held over Labor Day weekend. Back in the 1970s and ‘80s, it seemed like the largest Indian gathering in the world. It wasn’t. But I remember the many rows of teepees, tents, RVs, and camper trailers that filled the powwow grounds. There were also hundreds of dancers, ten or twelve drum groups, and twenty or thirty vendors selling popcorn, cotton candy, T-shirts, hamburgers, hot dogs, fry bread, snow cones, cheap toys, and fake and real Indian arts and crafts.

There used to be a rodeo during every powwow, complete with crazy Indian cowboys riding crazier bulls.

I remember those powwow nights were cold while the days were so hot that we Indian kids took off our T-shirts and drank water from a hydrant maybe fifty yards away from the powwow grounds. There were also two or three metal troughs that were used to water livestock. But coyotes and stray dogs would also lap at any excess water that remained in those troughs.

Cattle, canines, and Indian kids all drinking from the same source.

Randy and I were heading into the seventh grade. He didn’t know it yet but I’d already decided that it was going to be my last year at the tribal school. I’d begun to gather the courage to transfer to the white farm town on the reservation border. A much better school. A school that would better prepare me for college.

But, during that powwow in 1979, I was still just a rez kid roaming the moonlit powwow with my best friend. And he was enraged for reasons that I don’t remember. And he was looking for a fight.

Even now, as I write this, I want to make this a story about justice. I want to invent a good reason for Randy’s anger.

Randy was very handsome so let’s say that he’d caught the eye of a lovely Montana Indian girl and that her jealous boyfriend was looking for a fight.

Let’s say that somebody’s Indian father had once pummeled somebody else’s Indian father and their sons were looking to begin a generational feud.

I could imagine dozens of reasons, Indian and not, for Randy’s fury but all I know for sure is that a party of Montana Indian boys were looking to make war on Randy and me. Powwow gossip said those boys were carrying knives. Randy wanted to find them and throw the initial punch but I was desperately trying to convince him that we should run. My house was only a mile away from the powwow grounds. We could quickly make our way to safety.

But those Montana Indians found us first. There were six or seven of them walking toward us. They were maybe fifty feet away. They were big kids. And there were too many to fight. Even Randy recognized that. So we turned and ran.

I’m not a fast runner. But I was fast that night. Randy and I ran into the darker parts of the powwow grounds. Then we jumped a fence, ran across the paved highway, and down the dirt road that led toward the Assembly of God Church.

Yes, the church that wanted to save our heathen souls was going to maybe save our terrified bodies.

As we ran toward the chapel, we could hear the foosteps of the Montana Indians behind us. I was praying that the chapel’s front door was unlocked though I’d guess that Randy was at least half-hoping it was locked tight. Then we’d have to turn and fight.

But the door was unlocked. Maybe it was always open for any troubled soul looking for comfort. We dashed inside and locked the door behind us. A moment later, that Montana war party crashed into the wonderfully thick door. They cursed at us and pounded on the wood. Then some of them circled around the small chapel and pounded on the locked back door. Some of them pounded on the windows.

I was crying with fear. I knew those Montana Indians were going to break into the chapel and beat us to death.

But then we heard a female voice shout, “Hey, you kids, get away from there!”

It was Mrs. B, the minister’s wife. She must’ve been standing on the front porch of their house that was just a little farther down that dirt road. Her voice got louder and louder as she walked closer to the chapel.

“Get out of here!” she yelled. “Go away!”

Those Montana Indians were an angry bunch looking to stomp dance on our faces but they were still just kids. And the minister’s wife, who was maybe five feet tall and less than a hundred pounds, was still an authority figure—a white authority figure—so those Indian boys ran away.

Then the minister’s wife knocked on the chapel’s front door. She hadn’t grabbed the keys on her way out of her house.

“Is there anybody in there?” she asked a few times.

Randy and I didn’t speak or move. I don’t know why we were suddenly afraid of Mrs. B. Neither of us attended her church but we’d known her for our entire lives. She was very kind.

Eventually, she walked back to her house. I don’t know how long Randy and I waited. Ten minutes? An hour? A whole lifetime?

“Let’s run to my house,” I said.

“Fuck that,” Randy said. “I wanna fight.”

“There’s too many of them,” I said.

“I know,” Randy said. “But I still wanna fight.”

“But we can’t run on the road,” I said. “They’ll see us for sure. We need to run through the woods.”

“Maybe they’re waiting for us in the woods,” Randy said. “We know these woods better than them. We’ll kill them.”

I started crying again. To save myself, I was going to have to run through a dark forest filled with Montana Indians. I knew if I hesitated a second longer then I might never leave that chapel.

“Let’s go!” I yelled, unlocked the door, and raced into the trees. Maybe Randy would’ve returned to the powwow grounds but my decision to run forced him to run with me.

And so we sprinted through the dark. I don’t know if those Montana Indians were chasing us for real. I doubt it. But I ran as if they were. And a few hundred yards into the forest, I tripped hard over something and went crashing into the underbrush.

“Get up! Get up!” Randy yelled as he pulled at my arms. But my leg was stuck on something. I looked down and saw that my left ankle was tangled in barbed wire. I’d somehow managed to run into a three-foot stretch of barbed wire hanging between the last two posts that remained of an ancient and abandoned fence.

“Get up! Get up!” Randy kept yelling.

I knew those Montana Indians would catch us if I didn’t get to my feet soon. Randy knew it, too. So he and I tugged at that barbed wire together. We pulled it off my ankle. And the barbs gave me minor scratches and one ragged cut.

I was bleeding as Randy and I ran into my house. We rushed downstairs into my bedroom, collapsed on the floor, and laughed and laughed. We were boys. We were little warriors. We were finally safe.

Were those Montana Indian boys carrying knives as they chased us? Highly doubful. Would they have seriously harmed us if they’d caught us? Also highly doubtful. Randy and I would’ve taken a few punches and kicks, for sure, but we would’ve worn our bruises like war paint.

That next afternoon, we returned to the powwow. We didn’t see those Montana Indians again.

A year later, I did indeed leave the tribal school for the white farm town on the rez border. After a couple years of estrangement, Randy and I became friends again though we’d never be as close as we were in our childhood.

36 years and 3 months after our powwow escape, I received the phone call that Randy had died that morning in a car wreck.

I’m still in mourning. I mourn for the friendship that we had in our youth. I mourn for the friendship that had to change when I left the rez. And I mourn for the adult friendship that Randy and I never sought to make stronger.

If he were still alive, I’d email him this essay at his job. I have no doubt that Randy would heavily disagree with many of my memories from that night. And I’m sure he would say, “I still wish we would’ve fought them Montana Indians. You could’ve kicked the ass of the smallest one and I would’ve taken the rest.”

For decades, Randy had worked for our tribe’s fish hatchery. Their ultimate goal was to repopulate the Spokane River with wild salmon—the sacred fish that was taken from us when the Grand Coulee Dam was constructed from 1933 to 1942.

I know that I can’t resurrect Randy and bring him back to our river. But I can keep bringing him into my stories.

Look! He’s in your memory now. He’s the beautiful, loyal, and wild Indian boy running with the wild salmon. Watch him shimmer as he swims toward you, toward me, and then away.

Wow. I teach "The Absolutely True Diary..." and will work to incorporate this story into my class. It's generally the most liked book we read for many reasons but the truth in your writing is one of the big ones. Thank you for continuing to share your stories.

You did resurrect him though, and a piece of intense memory of your experience with it. I’ll mourn him with you. I’ve loved wild boys.

You are a good man and a powerful storyteller.