Returning the Gift

a look back at a historic event for Native American writers

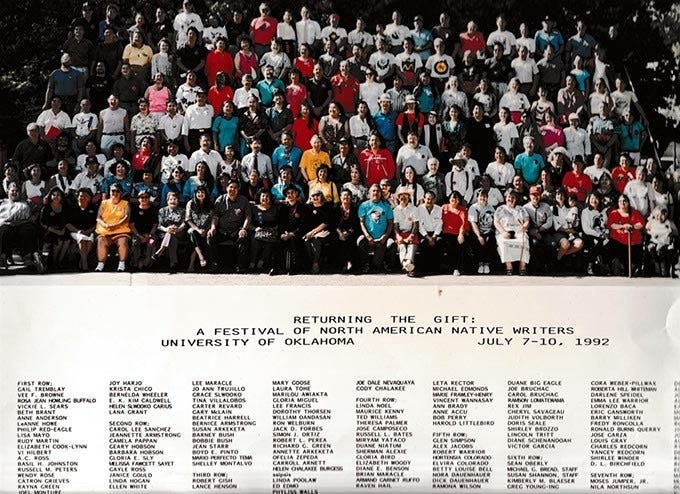

In July, 1992, over one hundred North American Native writers gathered in Oklahoma City for Returning the Gift (RTG), the first and only event of its kind.

I was 25 years old. My first book of poems and stories, The Business of Fancydancing, had been published to great acclaim that March. The New York Times Book Review gave me this review:

In this process, perhaps the most commanding voice will belong to Sherman Alexie, a Spokane/Coeur d'Alene Indian, whose first publication, "The Business of Fancydancing," is so wide-ranging, dexterous and consistently capable of raising your neck hair that it enters at once into our ideas of who we are and how we might be, makes us speak and hear his words over and over, call others into the room or over the phone to repeat them. Mr. Alexie's is one of the major lyric voices of our time. He is also one of the most forgiving of those who see farthest.

So, at Returning the Gift (RTG), I was the center of intense praise, jealousy, outright malice, and kindness.

I had left college the previous year three credits short of a degree and had been living back home on the Spokane Indian Reservation. I don't know how many of those Indian writers had traveled to RTG from their basement bedroom in an unfinished HUD house across the street from the tribal school, but that's who I was.

During those three days in Oklahoma City, I met many types of Indians for the first time: Indians who'd graduated from Ivy League universities; Indians who lived in the fabled cities of Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York City; Indians who were painters and sculptors as well as being writers; and even a few Indians who lived overseas.

I met cosmopolitan Indians and that really freaked me out. It made me feel like I’d just returned from burning down a U.S. Cavalry fort.

I also met many of my Native writing heroes in person. I especially remember my first conversation with the late Adrian C. Louis (1946-2018). He was a Paiute writer who remains one of my favorites. We'd only been penpals and I was happy to see that he was just as grumpy, profane, and funny in real life as he was on the page. The previous summer, he’d sent me an unsolicited fifty-dollar bill after I’d lamented that I'd become what I most feared becoming: an adult who’d quit college and was unemployed on the rez.

Adrian had included a handwritten note with that fifty-dollar bill: “Buy some typewriter ribbons and keep writing your poems."

At RTG, I also met pretend Indians—pretendians—for the first time. Looking at that old group photo, I'd estimate there were at least fifteen of them. Growing up as an Indian, I always knew about the people whom we called Wannabes—those non-Indians who hovered around Indian communities and cultures. They were a sad and powerless bunch. We mocked them. So I was greatly surprised to learn that many of those pretendians were powerful figures in the Native literary world. They were like Wannabes 2.0. I'd talk to those pretendians, note their inability to present and follow Indian social cues, look around puzzled, and think, "Why doesn't everybody know this person is faking it?"

Well, it turns out some of those pretendians in Oklahoma City are still getting away with it and there have been multiple waves of successful pretendian writers since 1992.

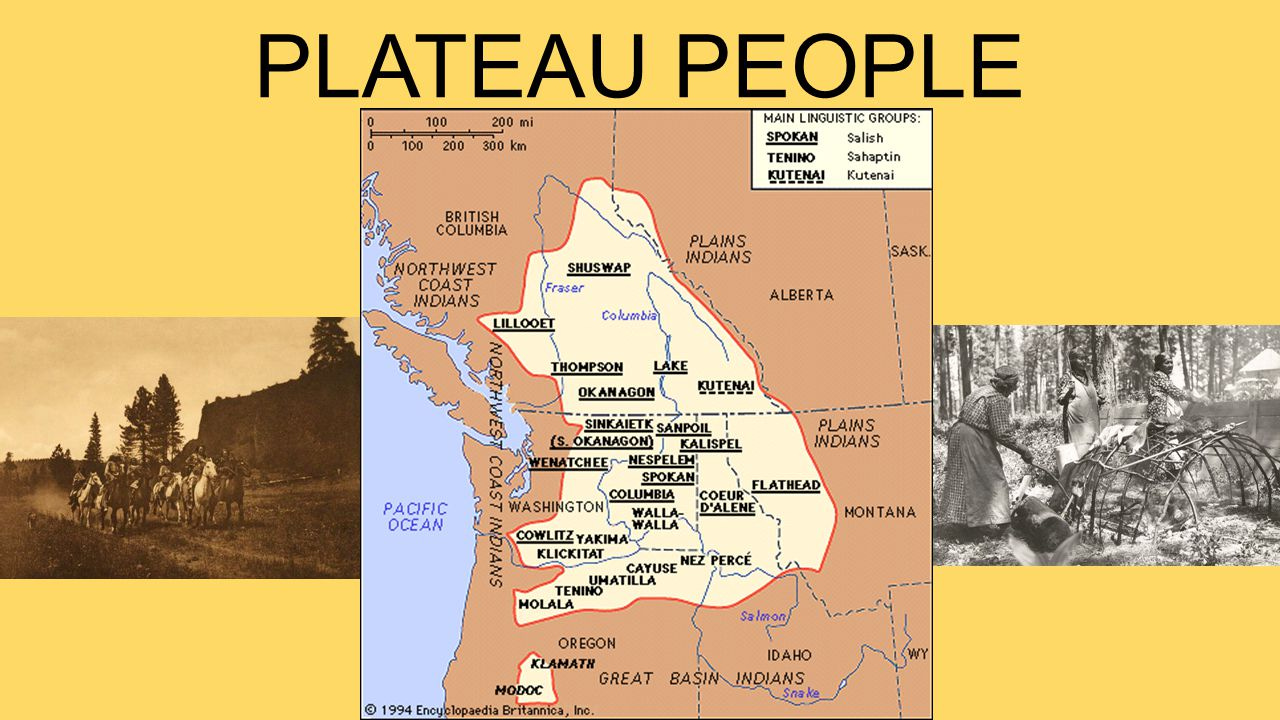

But it's not my encounters with pretendians that were the most memorable parts of RTG. I spent the greater share of my time with other Native writers from the Pacific Northwest Plateau Tribes. We had a super time. We'd all written many, many poems about wild salmon.

One night, I socialized in a bar with other Plateau Indians and other Indian writers that we'd dubbed Honorary Plateaus.

I was an alcoholic who'd only been sober for 13 months so I was nervous about being in a bar, especially since more than a few of the other Indian writers seemed to have their own drinking problems. But I managed well that night and I’ve been sober now for 33 years.

I should also note that the bar was also crowded with white people. It was a white bar. Like I said, I grew up on an Indian reservation in rural America so I was reflexively and consciously on the lookout for racist aggression. As I’ve written and said many times, 99% of white folks are just people living their ordinary and peaceful lives but it’s that hateful 1% who are dangerous.

And then it happened.

One of those white guys put his coin into the jukebox and played this song. Go ahead and watch/listen. It's a charming little ditty that also happens to be as racist as fuck, especially when employed as a weapon against a tableful of Indians in a white bar.

To give credit where credit is due, some employee pulled the plug on the jukebox maybe thirty seconds into the song. In the meantime, I'd risen from my chair and was fully ready to brawl. I hadn't been in a fistfight in years but I'd been rez-acculturated to throw punches. Those racist white assholes would've won the fight but I would've fought hard. Or, if nobody had thrown punches, I would’ve been throwing their curses back at them.

But then I looked at my fellow Indian writers and saw that none of them were standing. They weren't ready to fight. They were angry, scared, and humiliated but they'd also grown up in places where punches weren't thrown for any reason. Or, more likely, they were the kind of Indians who didn’t punch anybody, not even the Indian bullies.

I couldn't fight the racists alone so I stood down. We all paid our bills and left the bar. Outside, we immediately began joking about what had just happened. Indians can laugh even in the worst of times about the most tragic of events. I was shaking with laughter, sure, but I was also shaking with fear and embarrassment. I’d been willing to fight because of a dumb song. I could’ve ended up in the hospital or in jail. Dangerous foolishness. But it would’ve been justified, right? I would’ve been defending Indians—every Indian who’d ever been abased. Even now, in thinking about that night, I feel such anger.

Some incredibly smart Indians had been mocked by white dipshits in an Oklahoma City bar. I have the retroactive wish that I could count coup on those dipshits by smacking their heads with a copy of The New Times Book Review.

Yeah, I can joke about my anger. I can tell jokes about anything. I’m an Indian. That’s what we do.

Here's an old classic Indian joke—a dumb pun—that is also incredibly dark:

Q: Why is that Indian limping?

A: Because he wounded his knee.

I was completely exhausted when I traveled home after RTG. I’ve remained friends with some of other writers but most others have drifted out of my life for personal and professional reasons.

And, now, as I write this, I'm singing Hank Williams. My Dad used to sing this particular song when he was drunk and sad. You see, my father was indeed a “lonely Indian who never went nowhere.”

I could play you a hundred tunes from the alcoholic Indian father jukebox but no song hits me as hard as “Kaw-Liga.” My drunk father would serenade us with that sad and racist ballad

I know all the words by heart. I can almost sing it in key. We Indians were so desperate to be seen and heard that we turned racist songs into gospel.

Don’t you know that rez Indians are perfectly willing to spit at our faces in the mirror and kick our shadows in the balls?

So I wasn’t like approximately 97% of those Native writers at RTG in Oklahoma City. And I’m still not like them.

Some of us grew up on the frontlines of being Indian. We were children called into battle. Almost all of us are still in mourning.

A fine piece! So interesting that some of the biggest pseudo-Indians are seated in the front row! (I prefer that term to pretendian, which is too cute and undermines the seriousness of the issue, just as the word "nicknames" has been widely used to soften the blow to the reader/listener only of redfacing, cultural appropriation, mascoting , identity theft, but that may be why it's being used so broadly--so that the offense will be seen as a lesser one. Pseudo-Indian comes from the first incarnation of the Indian Arts and Crafts Act in the 1920s, called the Pseudo-Indian Act, which made it a criminal offense to impersonate a Native person. The legislative proposal came out of John Collier's Native rights work with the Northern Pueblos and others in NM, with Georgia O'Keeffe, D. H. Lawrence, Zitkala-Sa and other luminaries to stem the rising tide of whitemen posing as Pueblo, Apache and Navajo artists and selling clay pots, woven rugs/textiles, paintings and jewelry as their own work, and that's continues today, although there are some legal remedies and deterrents.)

A bit of background to that RTG gathering. Rayna Green (on front row of photo), who made a federal career and draws a substantial pension from her pseudo-Cherokee deceptions (claimed to be a Cherokee Nation citizen from Oklahoma and that Cherokee was her first language (in actuality, all her ancestors traced back to Europe, Cherokee Nation did not claim her, she speaks English only is a white Texan and was one of the most committed defenders of her fellow pseudo-cherokees, Ward Churchill and Jimmie Durham, and denouncer of those who successfully unmasked them. Before RTG, she had edited a book of Native women's poetry to promote her then Native girlfriend.. She was unmasked by Dr. Bea Medicine (Sihasapa Lakota), an anthropologist and educator, and her relative, Vine Deloria, Jr., Esq. (Standing Rock Sioux), author, historian, theologian, lawyer, educator, with Dr.Alfonso Ortiz, Dr. Michael Dorris and others....and Bea organized a bunch of us to boycott her book and decline our invitations for our work to be published in Green's book. RTG was seen as Green organizing a platform for her own promotion as a force in Native women's literature and as protective coloration for her continuing masquerade as Cherokee (I think she was given many awards from RTG as an outstanding Indian writer. Hope this little bit of background helps to give an idea of the scope of this thing.