Alex Kuo—my first writing professor, my father figure, my friend—recently died. And, in my grief, I’ve been unable to write. These are the first words that I’ve written in ten days.

In January, 1988, at Washington State University, I took my seat in a creative writing class—a poetry class. I was a new transfer student, arriving at Washington State to renew a romantic relationship after a previous relationship had ended.

I was a binge-drinking alcoholic with untreated mental illness. I was a poor reservation Indian boy—scarred in a thousand ways. I was goddamn smart and impulsive and goddamn stupid and impulsive.

That poetry workshop was crowded. There must’ve been forty students crammed into that small classroom. A few people had to stand. A few others sat on the floor.

A handful of those poets would become my friends. Some of them were already friends with one another and would later admit me into their cliques. I fell in love with a few of them. Maybe they loved me back. That’s what happens in creative writing classes. The love poems arise from love and they create love.

And lust, of course. Writers are lusty. At least, they used to be lusty. These days, the poets are afraid of their personal vulnerability. So they turn all their love and lust into political vulnerability. But it’s easy to be afraid of the government. It’s much harder to admit how much you fear yourself.

And, oh, think of how many poems are written because of unrequited love. Hell, poetry, the word, is just another synonym for unrequited.

But I didn’t know any of that as I sat in that classroom for the first time.

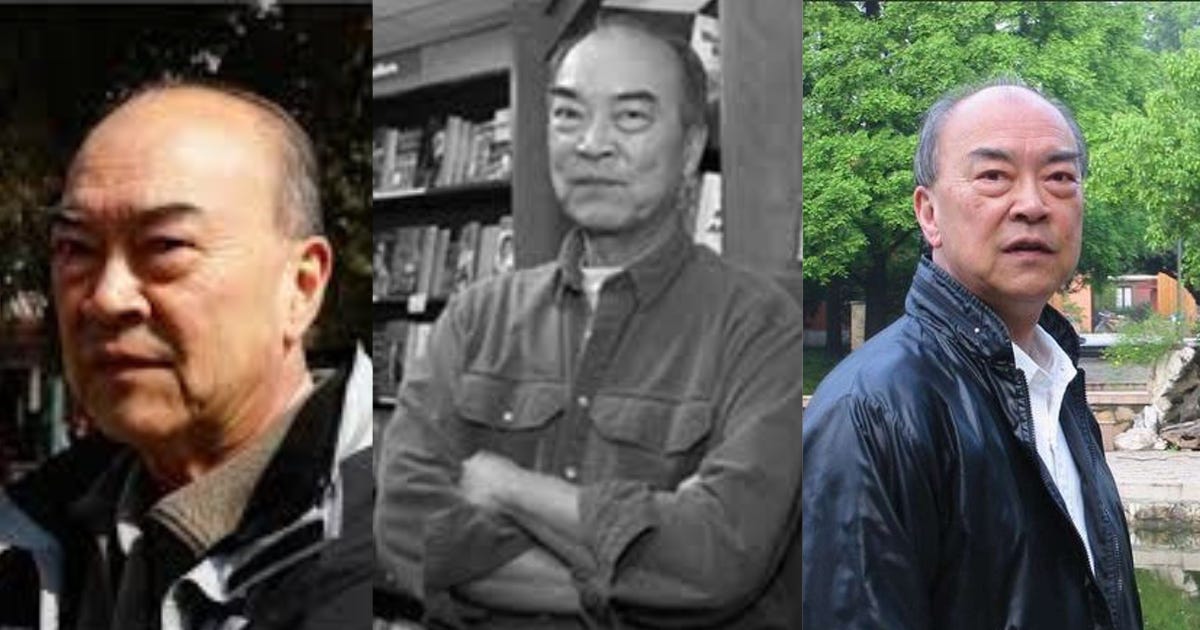

Five minutes late, Alex Kuo walked in and stood at the podium. Tall, handsome, and intimidating. He smelled of lunchtime whiskey and cigarettes. And something sweet. Something cinnamon. He studied the room. Studied the students.

Then he took a sheet of paper from his coat pocket and said, “I have the roll of students here. All your names. I’ve been teaching creative writing for thirty-two years and I can tell what kind of poet you are just by looking at you. When I call your name, I’m going to write down the grade I think you’ll earn in this class. I’ve done this for decades. And I’ve been 90% accurate.”

Then he proceeded to do just that.

Because of my last name, Alexie, I was the first name he called.

“Alexie,” he said.

“Here,” I said.

He stared at me for a long moment and then wrote down his prediction.

I thought it was hilarious. It felt like something that a sports coach would do. So, as a jock, as a lifelong basketball freak, I loved it. But I saw other students grow increasingly panicked. A couple of them immediately left.

After he finished the roll, Alex dismissed the class. We’d only been in class for twenty minutes.

The class met only once a week. Tuesday afternoons from 1 to 4 pm.

And only half of us brave souls returned the next week for the second class.

Later that semester, when I asked him about his predictions, Alex said he’d improvised all of it.

“There were too many students,” he said. “You can’t run a good workshop with that many students. So I had to figure out a way to get students to drop the class. Especially the students who couldn’t handle the critiques. The ones who only want praise.”

Some of you are probably offended by Alex’s improvised filtering system. I know that many of you—maybe most of you—are always in search of a supportive writing community. You search for formal safety. For critical safety. I understand that desire. I empathize with that desire.

But I’ve always been a ferocious writer. I’ve always been a ferocious person.

In high school, I played half of a basketball game with a cracked jaw. A few hours after the game, in the hospital, my coach asked me why I kept playing and I muttered through clenched teeth, “Because I wanted to win.”

He nodded his head. He understood. In later years, he’d tell my broken jaw story to motivate his teams.

I’d be proud if my official Indian name was Broken Jaw.

In more general terms, let me put it this way: You wouldn’t be reading this elegy if I’d only been a gentle person, if I hadn’t been the hyper competitive fighter that I am.

So Alex’s threat that he could predict his students’ grades resonated with me. It was a challenge that I immediately loved.

So I was disappointed when it turned out to be a bureaucratic move. And, yet, it still established that our workshop was going to be serious. It was going to be professional. It was going to be fierce.

We were only undergraduates but we were required to research literary magazines during the semester and submit poems to three that we thought might publish us.

Talk about terrifying!

A few more students dropped the class when they learned that submitting poems was a requirement.

Alex said to the class, “Why should I take risks with your poems if you’re not going to take risks?”

During the second week of class, Alex said, “You’re all going to submit a new poem to my office on Thursday morning. Slide them under my door if I’m not in. I’ll compile them into one manuscript and you can each pick up a copy of the manuscript from Nellie, the English Department secretary, on Friday. Read the poems, study the poems, and come next Tuesday ready to discuss them.”

A few more students dropped the class rather than submit their poems. I skipped all my other classes and wrote the first draft of this poem:

We lived in the HUD house for fifty bucks a month. Those were the good times. Annie Green Springs fortified wine was a dollar a bottle and my uncles always came over to eat stew and fry bread to find God in the sweatlodge to spit and piss in the fire. No one never had no job but we could always eat commodity cheese and beef and Mom sold her quilts for fifty bucks each to whites driving in from Spokane to buy illegal fireworks. That was the summer I found a bagful of real silver dollars and gave all my uncles all my brothers and sisters each one and no one spent any no one

Again, because of alphabetical order, my poem was the first one in the manuscript. I was going to be the first lab rat. So I was exhilarated and terrified when I sat in the classroom that next Tuesday afternoon.

Then I was startled when Alex walked into the classroom, immediately approached me, and asked if he could speak to me in the hallway.

“Okay,” I said, assuming that my poem was so shitty that he was going to ask me to drop the class.

In the hallway, he asked me what I was going to do with the rest of my life.

“I don’t know,” I said.

“I think you should write,” he said.

At first, I thought he was kidding. I expected him to smile. But he remained serious.

“I mean it,” he said. “You should write.”

I didn’t know what to say.

He pulled a hard candy out of his pocket, unwrapped it, and plopped it into his mouth.

I smelled cinnamon. Ah, that’s why he always smelled of cinammon. Alex loved cinnamon. He was a chain smoker. He drank too much. He was a leftist. His romantic relationships had always been tumultuous and would remain so until he found love with his longtime wife, Joan. He played favorites with his students. He led us on group camping trips. He took us to bars so we could party with visiting writers. He clashed with university officials, department chairs, and other professors. He was vain and generous. Formal and inappropriate. Hilarious and secretive. Welcoming and judgmental. Ambitious and jealous. So complex. So contradictory. So beautiful, so very beautiful.

And, of course, I saw in him all the contradictions that I too often fail to see in myself. And I quickly forgave him for all the weaknesses that I continually punish myself for also having.

“What are you going to do with the rest of your life?” he asked me again in the hallway outside the classroom.

“Who do you want to be?” he asked.

It was the first time that we’d ever spoken but he was already asking personal questions.

I didn’t know what I wanted to become.

“Shit,” he said and looked past me to my future. “I’m sorry but you are gonna be a writer.”

He was apologizing to me for the glory and agony that was destined to come my way.

He knew.

He knew.

I had dinner with Alex and Joan a few months ago. We hadn’t talked in quite a few years, entirely because of my actions and inactions. We weren’t estranged. My life had just become much smaller.

As usual, at dinner, Alex and I were writers who could write emotionally but were unable to fully express our emotions to the loved one sitting next to us.

I wish that I would’ve said, “Everything that I am as a writer is because of you, Alex. I’m a poet because you said that I was going to become a poet.”

I wish that I would’ve said, “And for everything that my writing life has been, I say ‘thank you’ and ‘fuck you’ for believing in me from the first word that I wrote.”

We would’ve laughed.

He would’ve nodded his head.

He would’ve said, “That’s goddamn true.”

And now, as I think of how I might end this elegy, I can smell cinnamon.

And I can feel the power of words.

Because I bet that you can smell cinnamon, too.

I cannot become a paid subscriber,.

I wish I could.

My bills cannot be paid.

But...Your post today... your elegy...is that an elegy...has touched me.

Alex was right. Alex ws correct.

Bless the day you walked into his class.

Thank you for your post.

Oh my God. I love this so much! There are some teachers you just never forget. This is a beautiful essay!!