In 2003, after years on the machine, my father, Sherman Alexie, Sr., chose to quit dialysis. He chose to die. He’d never been on the kidney transplant list because he couldn't stop drinking for more than a few months at a time.

Two of his dialysis nurses came to his funeral. They hugged my mother, siblings, and me.

"Your father was so shy and funny," one of them said.

Shy and funny. It seems somewhat odd to link those two qualities together. Has a court jester ever gone on a silent retreat? But "shy and funny" is an accurate description of my father. And, yet, shy can be an armor that keeps people at a distance and funny can be a shield that pushes people away.

At my father's funeral, a number of reservation Indians stood, gave their remembrances, and spoke of not really knowing my father.

One old Indian man said, "I'd see Sherm two or three times a week getting the mail at the post office. He'd wave. I'd wave. That happened for years. He was a nice guy."

Maybe my father's Indian name should've been Sherman Gets the Mail. Maybe his Indian name should’ve been Sherman Unknowable.

Once, during a podcast, the host asked me what my late father did for a living. And I said, "He watched TV, read spy and western novels, and did crosswords."

Then I added, "He mostly stayed in his bedroom. At mealtime, he'd come out, load up a plate, and bring it back to his bedroom. For him, every plate ended up as a TV dinner tray."

Then I laughed and said, "I also spend most of my days watching TV, reading novels, and doing crosswords alone.”

I often tell aspiring writers that the best part of writing is the solitude.

I also tell them that if they want to have a successful writing career—the career that brings the book sales, awards, and literary fame—then they should prepare themselves for the loneliness. You write alone; you read alone; you're in the taxi, Uber, or Lyft alone; you're in the hotel alone; you're on the college campus alone; you're in the bookstore alone; you're in the TV station alone; you're in the radio studio alone; you’re on the train alone; and you're in the airport alone.

I tell them, "If you want to be a great writer then you need to be great with loneliness."

What's the difference between solitude and loneliness? One is where you search for God and one is where you order room service.

Over the last thirty years, I've flown almost two million miles as a writer. I'm a writer with wings. On one wing is tattooed "Life!" On one wing is tattooed "Life?"

Do I wish I'd flown less? Do I wish I'd spent more time at home? Yes and yes. But I also love my career as a writer. I love to be onstage. I miss being onstage. I'm a storyteller. And I'll make the sacrifices necessary to meet and greet the people who want to hear my stories.

I think most every writer wants an audience. I think almost every writer desires an audience. And I don't mean desire as in sensual. I mean it as spiritual. Or maybe, for a writer, sensual and spiritual are almost synonymous.

And doesn't everybody want to be a writer? Don't they want an audience? Even if it's just an audience of one?

Yesterday, in a coffee shop, I eavesdropped on a middle-aged man on a coffee date with a younger man.

"Do you make money on your art?" the older man asked.

"Not yet," the younger man said.

"I've self-published two books," the older man said. "One called Warrior Dog, about a dachshund that gets in adventures after the apocalypse. And I wrote a memoir called Obfuscated Man, about a boyfriend who broke my heart in the 80s."

My first thought was Getting your heart broken is apocalyptic.

My second thought was I wonder if that guy knows that obfuscated is a past tense verb and not an adjective.

My third thought was That guy has owned many dachshunds.

My fourth thought was I wonder if that younger guy has father issues.

My fifth thought was That older dude's need and want to be seen as a writer is boiling all the coffee in this shop.

My father was only a writer when he was drunk but only when he was still intelligibly drunk—when his creative inhibitions had less power over him.

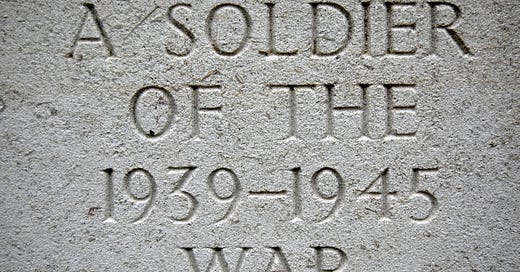

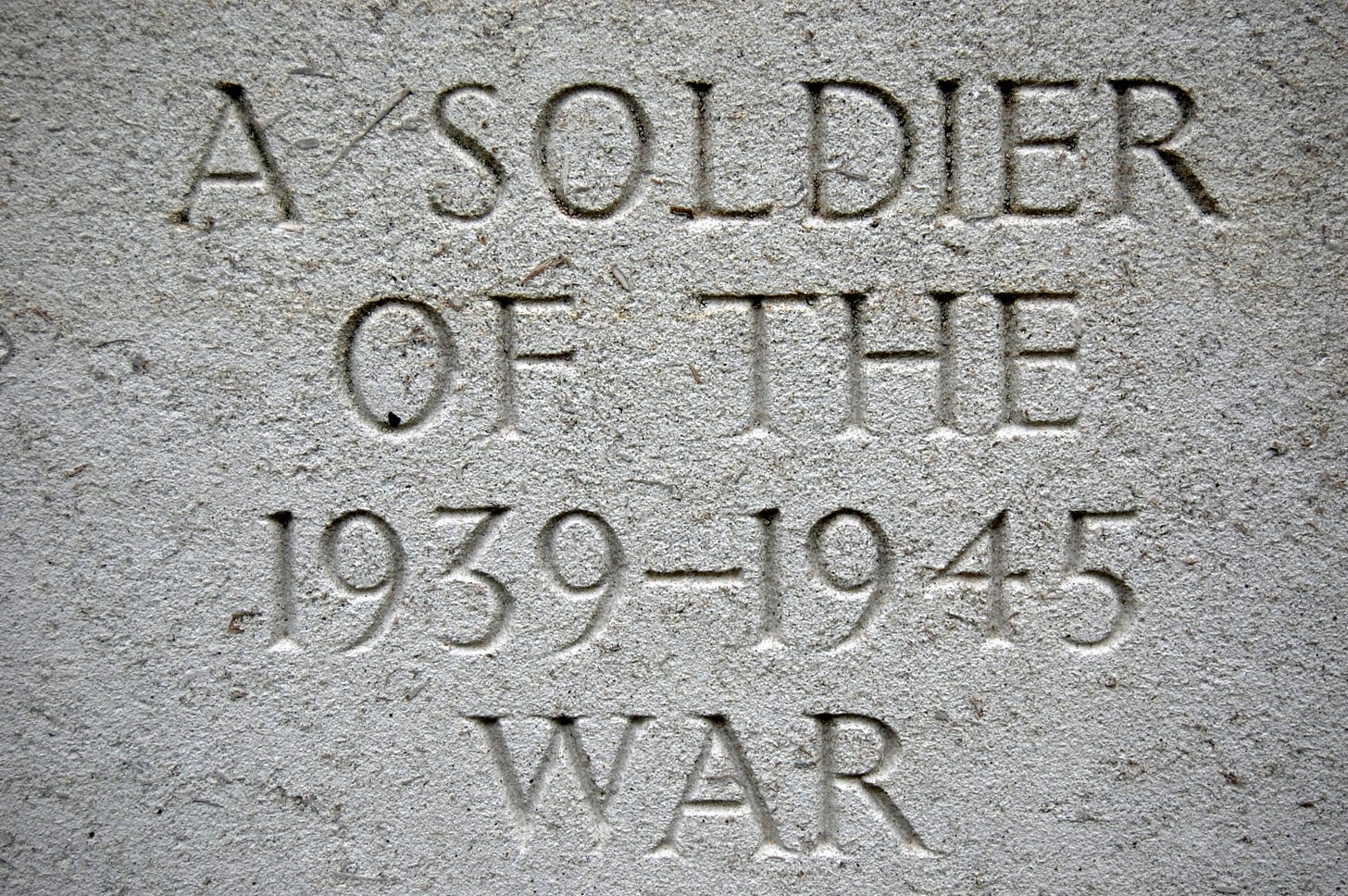

My father was seven when his father was killed in action on Okinawa on April 5th, 1945. Seven months after that, my father's mother died of tuberculosis.

My father was a war orphan raised by his grandmother.

And my father's novel was about a Native American war orphan raised by his grandmother in Seattle. In the first chapter, he meets a Japanese American woman, a first generation immigrant whose Japanese father was also killed on Okinawa during World War 2 and whose mother also died of tuberculosis. Yes, the Japanese American woman was also a war orphan.

My father never finished his novel. As far as I know, he wrote and rewrote only the first chapter. He penned it by hand and, when he was coherently drunk, he'd pull the handwritten pages from a drawer and read them aloud to us, his children, his two sons and two daughters.

In the first chapter of my father's novel, the Native American man and Japanese American woman are on a date. They talk about their dead fathers. They talk about their dead mothers. Who talks about their fathers and mothers on a date? Everybody should! It's the best way to guess at the future. The Native man and Japanese woman are sweetly awkward as they careen toward romance. They laugh about racism. They laugh about how often Native Americans on the West Coast are confused for Asian Americans. Yes, they spend the date laughing. It's a good date.

At the close of evening, the Native man walks the Japanese woman to her apartment building in downtown Seattle. They kiss good night.

And then one war orphan says to the other, "I wonder if your father killed my father on Okinawa."

And that was the end of the first and only chapter. My father left us with a cliffhanger. And, after his death, we couldn't find those handwritten pages.

I've often thought of writing that novel, of finishing my father's novel. If I ever do, I'm going to put both of our names on the cover. The novel will be titled Indian Summer, Indian Winter and its authors will be Sherman Alexie, Jr. and Sherman Alexie, Sr.

Right now, as I ponder that book, the first sentence is "My father was a shy and funny man who was killed in action during World War 2."

The second sentence is "Seven months later, my mother died of tuberculosis, a death that might be as painful and bloody as a soldier who is killed in action."

The third sentence is "So I’m a war orphan who’s vowed never to go to war."

The fourth sentence is "But I've never stopping waging war on myself."

I think that the whole story is right there in that one chapter. I like it ending right where it does, leaving us wondering. Thank you, Sherman.

You are the reason I’m glad I got into Substack. Exquisite stuff.