Adolph Alexie, my father’s father, was killed in action on April 6th, 1945, on Okinawa. He earned a posthumous Bronze Star for heroic service in a combat zone.

Six months after he died, his wife Susan died of tuberculosis. So my father, Sherman, Sr., and his sister, Ellen, were orphans raised by their grandmother.

My father was a war orphan. My siblings and I were raised by a war orphan. The death of a soldier creates generations of loss.

I honor my grandfather’s sacrifice but I wish that he’d survived the war and made it back home to the reservation.

My father never talked about his father. My father never talked about his loss. My father never talked about his grief.

He was an alcoholic who died of kidney failure. I think that he drank to ease his pain. But that relief is only temporary. My father suffered. And we suffered with him though we couldn’t give it a name.

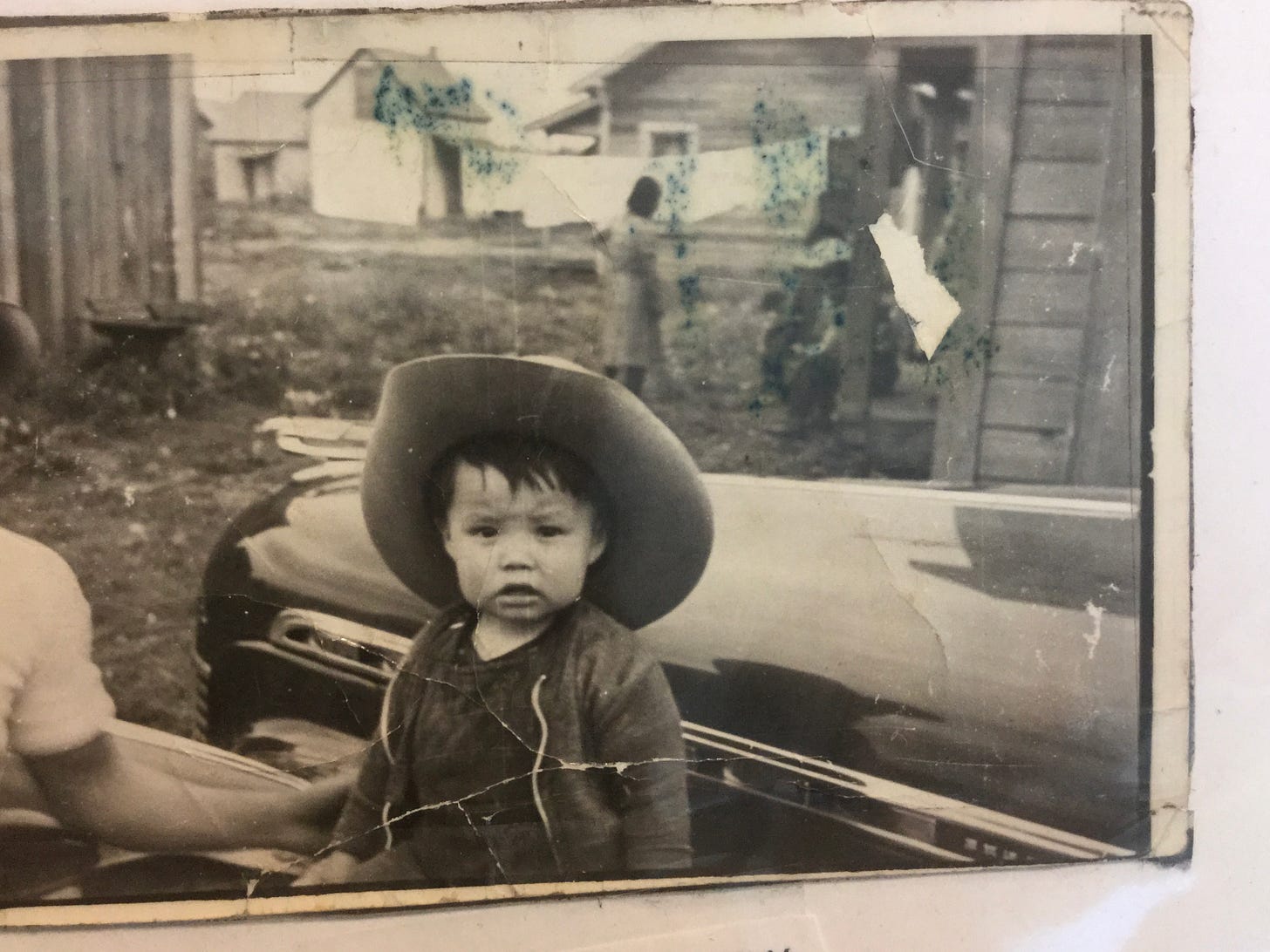

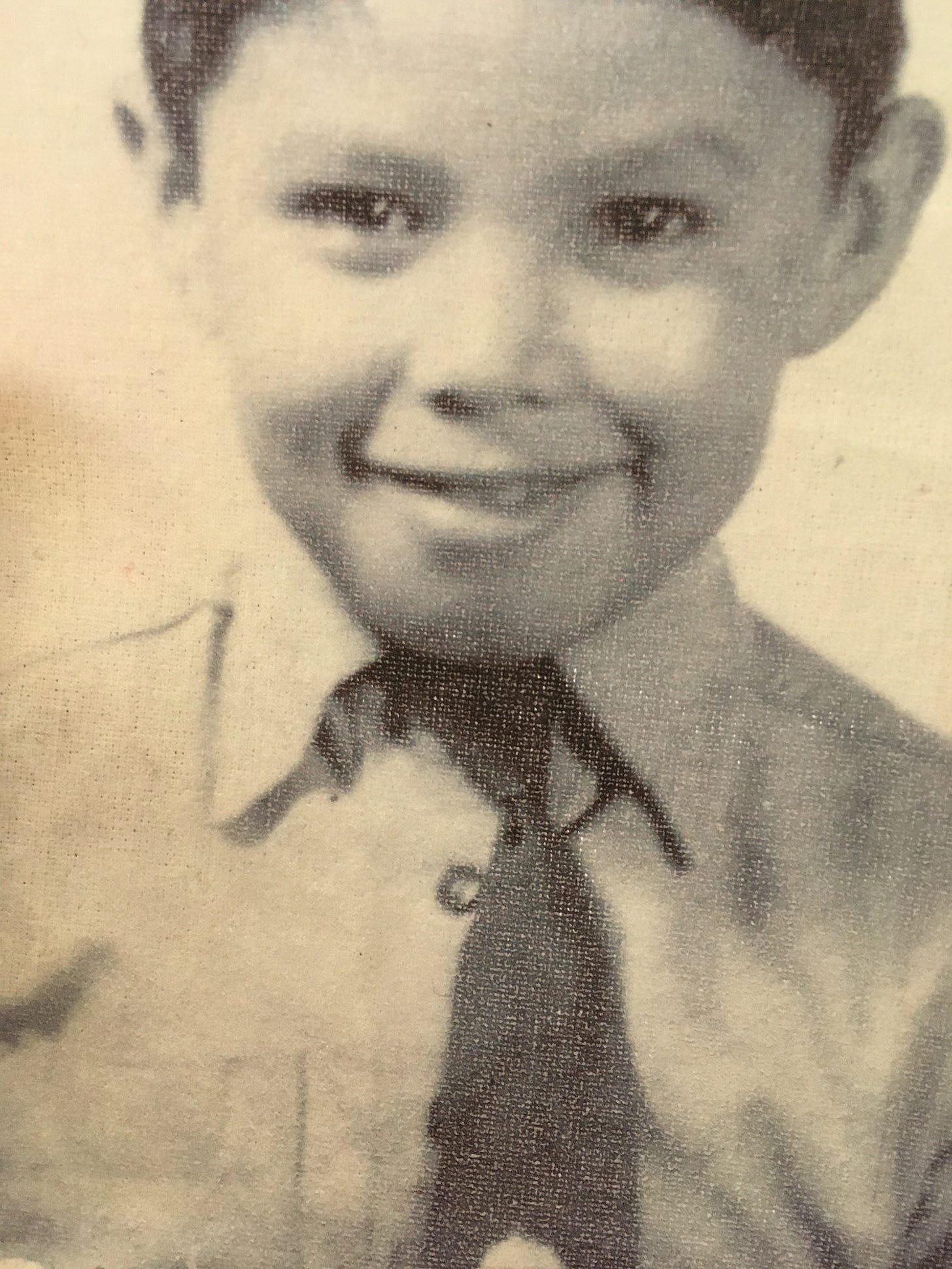

Here are some childhood photos of my father.

And this is my father not long before he died of alcoholism at the age of 62.

In 2003, after years on the machine, my father chose to quit dialysis. He chose to die. He was never on the kidney transplant list because he couldn't stop drinking for more than a few months at a time.

Two of his dialysis nurses came to his funeral. They hugged my mother, siblings, and me.

"Your father was so shy and funny," one of them said.

Shy and funny. It seems somewhat odd to link those two qualities together. Has a court jester ever gone on a silent retreat? But "shy and funny" is an accurate description of my father. And, yes, shy can be a citadel that can't be breached and funny can be a shield that pushes people away.

At my father's funeral, a number of reservation Indians stood, gave their remembrances, and spoke of not really knowing my father.

One old Indian said, "I'd see Sherm two or three times a week getting the mail at the post office. He'd wave. I'd wave. That happened for years. He was a nice guy."

Maybe my father's Indian name should've been Sherman Gets the Mail.

Once, during a podcast, the host asked me what my late father did for a living. And I said, "He watched TV, read spy and western novels, and did crosswords."

Then I added, "He mostly stayed in his bedroom. At mealtime, he'd come out, load up a plate, and bring it back to his bedroom. For him, every plate ended up as a TV dinner tray."

My father often isolated himself. I recognize now that he was depressed and suffering a war orphan’s PTSD.

And my father wanted to be a writer. Yes, another person trying to write his way out of his depression.

But he was only a writer when he was drunk—when he was still intelligibly drunk—when his creative inhibitions had less power over him.

For most of my childhood, my father worked on a novel.

The novel was about a Native American war orphan raised by his grandmother in Seattle—a man whose father was killed in action on Okinawa in WW2.

In the first chapter of the novel, the war orphan Indian meets a Japanese American woman, a first generation immigrant whose Japanese father was also killed on Okinawa during World War 2 and whose mother also died of tuberculosis. Yes, the Japanese American woman is also a war orphan.

My father never finished his novel. As far as I know, he wrote and rewrote only the first chapter. He penned it by hand and, when he was coherently drunk, he'd pull the handwritten pages from a drawer and read them aloud to us, his children, his two sons and two daughters.

In the only chapter of my father's novel, the Native American man and Japanese American woman are on a date. They talk about their dead fathers. They talk about their dead mothers. Who talks about their fathers and mothers on a date? Everybody should. It's the best way to guess at the future. The Native man and Japanese woman are sweetly awkward as they careen toward romance. They laugh about racism. They laugh about how often Native Americans on the West Coast are often confused for Asian Americans. Yes, they spend the date laughing. It's a good date.

At the close of evening, the Native man walks his date to her apartment building in downtown Seattle. They kiss good night.

And then one war orphan says to the other, "I wonder if your father killed my father on Okinawa."

And that was the end of the first and only chapter. My father left us with a cliffhanger.

I've often thought of writing that novel, of finishing my father's novel. If I ever do, I'm going to put both of our names on the cover. The novel will be titled Indian Summer, Indian Winter, and its authors will be Sherman Alexie, Jr. and Sherman Alexie, Sr.

Right now, as I ponder that novel, the first sentence is "My father was a shy and funny man who was killed in action during World War 2."

The second sentence is "Seven months later, my mother died of tuberculosis, a death that might be as painful and bloody as a soldier killed in action."

The third sentence is "I'm a war orphan who has vowed never go to war."

The four sentence is "But I've never stopping waging war on myself."

As a peacetime veteran whose parents were both alcoholics, I offer a prayer this Memorial Day for your father, for your family, and for you. And I hope you finish that novel.

I sincerely hope you get to a place where you can finish your father’s book! It’s got some great bones