How Steven Spielberg Taught Me How to Swim

essay

In the mid 1970s, my mother, Lillian Alexie, convinced our tribe to create a job for her. She was a powerful and persuasive person, and it was a great idea, so she become the Young Activities Director for the Spokane Tribe of Indians. Our reservation was an isolated place in those days. It remains an isolated place. But, in the 70s, every phone call to anywhere was long distance. And there weren’t many ways to entertain, distract, and educate us kids, especially during school breaks.

So, during the summer of 1975, my mother arranged for group swimming lessons for ten or fifteen Spokane Indian youth at the YWCA in Spokane, Washington. The lessons would be somewhat redundant. On my rez, Indians learn how to swim before Kindergarten. It was a social necessity. Our reservation is bordered by the Columbia and Spokane Rivers. Two lakes, Turtle and Benjamin, were popular places for swimming.

But none of us had ever swam in a fancy pool.

I was excited about the trip but scared, too. I didn’t know how to swim. I’d inherited my mother’s hydrophobia. I was afraid of water. I was also nervous about spending time in Spokane. It was the big city for us rez kids, filled with wonder and possibilities, but it wasn’t always friendly to its Indian denizens and visitors. And it was sometimes openly dismissive and hostile.

Once, while my parents, siblings, and I were standing at an intersection in Spokane, on our way from our motel to the nearby Kmart, a truck pulled up close to us.

“Fucking Indians,” the white driver yelled then leaned out the window and spit on us.

I was seven. My big brother was ten. My little sisters, twins, were six.

There is bureaucratic racism. There is economic racism. There is cultural racism. There is cluelessness that is mistakenly perceived as racism. There is universal misanthropy practiced by total assholes. And then there is the outright rage and hatred directed at a specific group of people.

As rez Indian kids, we learned how to practice defensive living in the anti-Indian parts of the world.

Even now, in the 21st Century, when traveling in Montana and South and North Dakota, my wife and I like to wear T-shirts and/or hats festooned with American flags. We know there’s very little chance that we’ll catch any shit for being Indian but wearing patriotic clothing is like wearing a seatbelt on airplanes. You gotta remember that turbulence is unpredictable.

When we Indian kids rushed into the YWCA for our first group swimming lessons, we didn’t face any blatant racism. White people stared at us. Some of them were obviously displeased. Their scorn might have been motivated by racism but it’s far more likely that they were simply reacting to our rambunctious entrance. All kids are feral. As rez kids, we were more feral than average.

In the locker room, we boys learned that we’d have to shower before we entered the pool. We also learned that our jean shorts were not approved swimwear so they allowed us to dig through the lost-and-found pile for proper trunks. Then we each ran into toilet stalls to change in private. No way we were going to be naked in front of one another or especially in front of strangers.

I vividly remember a kid named Mike saying, “Did you see all the hairy balls?”

Our laughter probably irritated the other men in the locker room. Rez Indians laugh often and loudly.

Then we exited the locker room to discover three young woman waiting for us at poolside. They were our swim instructors. At the time, they seemed very mature, though they were probably in their late teens or early twenties, not much older than we were. But they were city girls with jobs. All three of them were Asian, which seemed very exotic. But they were brown-skinned and had black hair so they also looked like us. They were wearing one-piece swimsuits. I’d never seen any female in a swimsuit in person. I was a little scandalized. On the rez, the women and girls swam in same kind of T-shirts and jean shorts that we boys did. So the rez girls standing among us at the Y poolside were wearing their own T-shirts along with swim trunks that they’d also chosen from the lost-and-found.

The three instructors introduced themselves but I don’t remember their names. So I’ll call them Emily, Elizabeth, and Anne.

“Okay, kids,” Emily said, “Let’s get into the pool.”

She and Elizabeth walked down the stairs into the shallow end of the pool. All of the other Indian kids followed them. But I was too scared to join.

Standing at poolside, I silently chastised myself for believing that I’d be brave enough to enter the pool once we were in the Y. I was often bullied on the rez. And I knew the other kids would bully me once we got home if I didn’t get into the water.

But I still couldn’t move. My fear of the water and my fear of future social ostracism grew exponentially.

Emily and Elizabeth led the other kids through some basic exercises in the pool.

I wanted to run away.

But then Anne approached me. She knelt so we were eye-to-eye.

“Hi,” she said. “I’m sorry. I forgot your name.”

“I’m Junior,” I said.

“Hi, Junior. I’m Anne.”

We shook hands.

“How are you feeling?” she asked.

“I don’t know to swim,” I said.

“Not at all?”

“I’m scared of the water.”

“That’s okay,” she said. “You’re okay. How about we just put our feet in the water?”

She led me to the pool’s edge. We sat beside each other. She put her feet in the pool and I did the same.

“Okay,” she said. “How about we just kick our feet?”

So for the next thirty minutes or so, Anne and I kicked our feet in the water and talked about life.

I don’t remember much about the conversation but I do recall her saying that we were the first Indians that she’d ever met. That made me feel somewhat exotic. And I told her she was the first Asian person that I’d ever met.

I also wanted to tell her that I’d fallen in love with her—with her patience and kindness—but I held back.

When the lesson ended, she shook my hand and said, “Maybe next week we can walk in the shallow end.”

I nodded my head though I doubted that I’d ever enter the pool.

In the locker room, the other Indian boys teased the shit out of me. Teased me for being afraid of the water. And accused me of having a crush on that Asian girl.

I couldn’t refute their insults. I was terrified of the pool and I did have a massive crush on Anne.

Without showering, and still wearing our wet clothes, including the borrowed shorts, we climbed aboard the bus, and my mother drove us home.

During the ride, I wondered if my new love for Anne would help me be brave enough to return to the Y.

But, that next week, none of the other Indian kids showed up for the bus ride from the rez community center to Spokane. Indians have been experts at quiet quitting for many decades before that concept was named. And Mom didn’t think it was a wise use of time and money for us Alexie hydrophobics to travel to the YWCA for a swim lesson.

So it was over.

I knew that I’d never see my dear Anne again.

I was heartbroken.

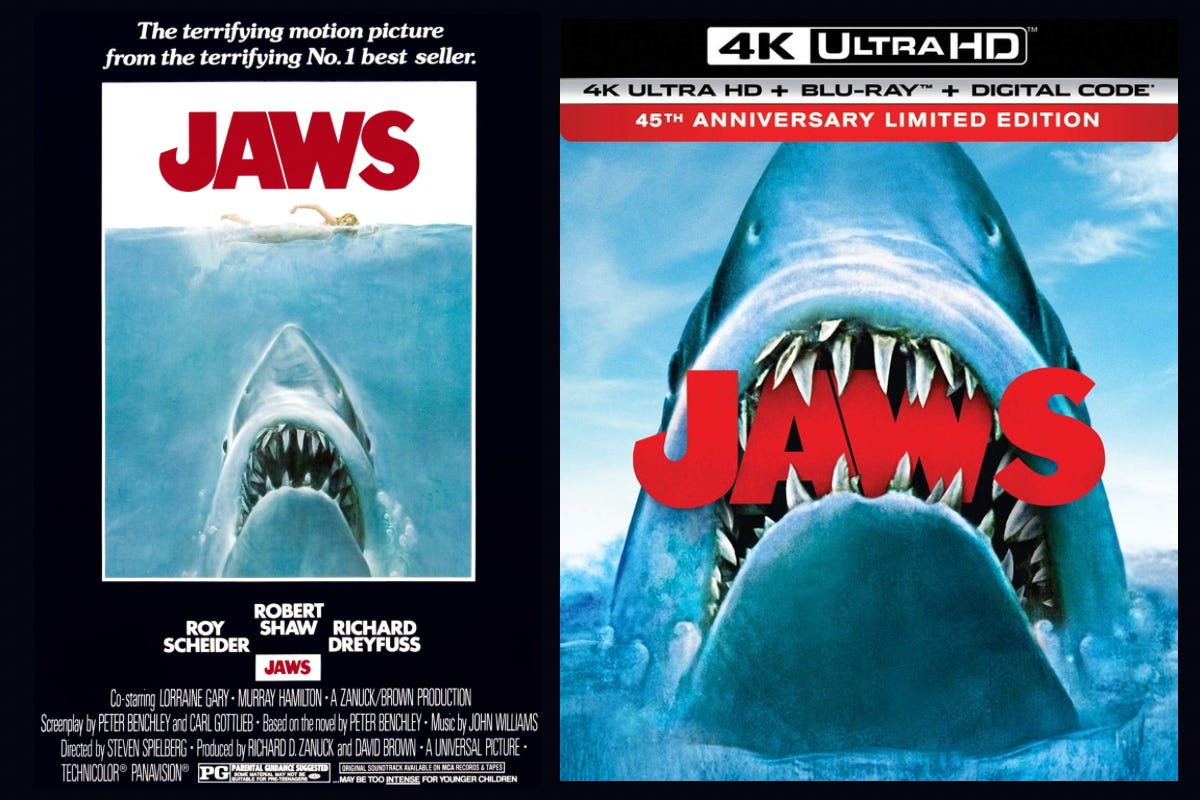

But then, a few weeks later, my family drove into Spokane to see Jaws, the classic horror film about a killer shark.

You know the movie. We all know the movie.

You might think that I, so terrified of the water, wouldn’t want to see a terrifying movie set at sea. But I’ve always been able to separate reality from cinema. I wasn’t afraid of the water flowing on the big screen. And you might think that I was too young to be seeing an R-rated movie. But, in my family, R meant “We R going to see that film.”

My family and I were shocked to discover that the line to get into the theater stretched around the block. Hundreds of people. It was Spokane so at least 95% of them were white. That was okay. We were used to being the only Indians.

But then somebody called out my name.

“Junior!”

It was Anne and the other two swim teachers, Emily and Elizabeth.

I was delighted to see all three of them but I was especially excited to see Anne.

“Junior!” she said again.

I walked over to them. Anne hugged me.

“Are you excited?” she asked me. “I’m so excited. I’ve never been this excited to see a movie.”

I wanted to say something clever about a swim teacher excited to see Jaws but I had no flirtatious abilities in those days.

“I’m excited, too,” I said.

Anne hugged me again. Nobody had ever been that happy to see me. She was so enthusiastic. I wouldn’t experience anything like that until my first serious girlfriend fell in love with me seven years later.

Then the Jaws line began to move. It was almost showtime.

“I gotta go to the back of the line,” I said.

“Okay, I hope I see you in there,” Anne said.

As I walked down that line with my family, I felt ecstatic because everybody else was ecstatic. Nobody looked at us Indians with any negativity. They smiled at us. We smiled back.

It was one of the greatest and most universal pop culture moments of all time and my rez Indian family were full participants.

We belonged.

So, okay, the title of this essay is misleading. I didn’t learn how to swim until my 50s. But Steven Spielberg, the director of Jaws, did something far more important for me. He taught me that a great movie can transcend real and imagined boundaries and borders.

He taught me that I could take my seat in a movie theatre and feel the power of a universal storyteller.

That’s what a common culture can teach us. And I’m sad that we Americans don’t have a common culture anymore. Or, at least, we don’t share nearly as much anymore. We’re brutally separated by race, gender, economics, and politics.

Is this time worse than other terrible times in American history? No, not at all. But that doesn’t mean we’re living in a good time.

I’m not happy with our culture. I’m disappointed in the people who share my politics and the people who don’t. I’m especially disappointed in all those fiction writers and poets who are writing bitter work that increases our separation from one another.

I don’t need happy endings in art. I don’t want happy endings in art. I don’t yearn for redemptive arcs. But I want us to write with more empathy. I want us to live with more empathy.

Am I being too romantic? Perhaps.

But I laugh when I see those leftists who write things like “Love is always the answer” but then follow that with social media posts that shout, “Death to fascists!” And these are often the same people who claim that words can be violent.

I guess some forms of violence are more acceptable than others. I know that some of you reading this want to end the death penalty that exclusively kills the poor but also celebrate the vigilantes who murder CEOs on city streets.

We all travel heavy with contradictions but some contradictions are worse than others.

I loved Jaws back then and I love Jaws now. I watch it at least once a year. It’s a perfect movie. But, as perfect as it is, it also turned sharks into villains, into apocalyptic monsters.

But here’s the thing: sharks are beautiful.

Let me repeat that: sharks are beautiful.

So maybe it’s time for all of us to remember that our enemies, no matter how dangerous we think they are, might be beautiful, too.

So beautifully written that I was transported back in time to your pool and movie theatre. Thank you for reminding us to speak with care and be open to all, no matter the politics, religion ....

People can be taught to write, but writing that engages the reader is a story, with tension, vulnerability, analysis and exquisite kindness- that’s your gift.