Dear Writers,

How successful do you want to be? Do you want to sell millions of copies? Do you want to win Pulitzers and National Book Awards? Do you want to see your book displayed on the front tables in bookstores? Do you want to stand onstage because “attention must be paid”?

In May, 1992, my first book, The Business of Fancydancing, was reviewed in The New York Times Book Review:

I was only 26 years old and working at People to People, a educational student travel service, in Spokane, Washington, when my editors at Hanging Loose Press faxed this review to my desk.

Yeah, I was in charge of the office fax machine. And I was the only male secretary.

(Hello, Brenda! Hello, Stacy! Hello, Cathy!)

And there I was—the minimum-wage white collar worker who was suddenly “one of the major lyric voices of our time”? Really? I couldn’t be. No way. I was just an Indian kid from the rez who was three credits short of a Bachelor's Degree in American Studies.

Hanging Loose Press was a small independent press in Brooklyn, NY. They’d printed only 1,000 copies of my book.

Sitting at my desk with that NY Times review in hand, I got dizzy. Then fully nauseous. And then I vomited into my garbage can.

Within hours, agents found my home number and began to call me. I had a landline and answering machine. After a while, I ignored the rings and let the machine do the answering. Nearly all of those agents scared the shit out of me. They were centaurs: half-art, half-capitalism.

I picked my longtime agent, Nancy, because she knew that one of my short stories, “The Lost Pilot,” had borrowed his title from a poem and book by James Tate.

Nancy knew poetry. Poetry has never been involved in any sort of successful capitalism. I love Nancy.

She and I worked together over the next 6 months to get my short story manuscript into shape. We added a couple of new stories and dropped a few others.

At the time, my manuscript was titled, Imagining the Reservation, an homage to Lawrence Thorton’s novel, Imagining Argentina.

In January, 1993, Nancy submitted my manuscript to multiple editors. A week later, there was an auction for the publishing rights. Morgan Entrekin, publisher of Atlantic Monthly/Grove Press, won the auction.

(During that auction, I constantly phoned a Native American woman to give her updates on the rapidly changing details. We’d only been on two dates. She was out of town on a business trip. Her name is Diane. We’ve been married for 32 years.)

After he won the auction, Morgan immediately suggested that the title of one of my short stories should be the title of the book. He was absolutely correct.

(By the way, look at the medallion, an homage to my book, that was designed by my big brother and beaded by my cousin:

Yeah, some Indians, like my brother and cousin, are impossibly cool.)

Then, a few months after that auction for my book, I published a short story in Esquire magazine.

I posed for that photo in my cousins’ wood shed across the road from our family home on the Spokane Indian Reservation. I’m wearing the photographer’s assistant’s sweater because its color looked better against that golden wood than whatever I’d been wearing.

We published the book in September, 1993, and it went bananas. Great reviews, great sales. I was an overnight literary star.

I went on a 15-city book tour.

(I proposed to Diane on that book tour. She said yes in Chicago).

Three times during that tour, one of my father’s high school friends showed up at a bookstore expecting to see him.

I’m named after my father. I’m Sherman Alexie, Jr.

Here are my father and mother in their teen years:

My father went to a Catholic high school in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. That school was almost entirely white. All of my father’s closest high school friends were white.

And my father had been so academically, musically, and athletically accomplished in high school that his three friends, seeing his name in their local newspaper, were unsurprised that he’d published a book that was receiving national attention.

But they were surprised to meet me, the son.

Those three white friends were a university philosophy professor, an investment banker, and the athletic director for a Pac-10 college.

When they asked me what my father was doing, I had to be honest. I said, “He’s a sporadically-employed and binge-drinking alcoholic living on our reservation. I love him. His stories are the primary reason why I’ve become a storyteller.”

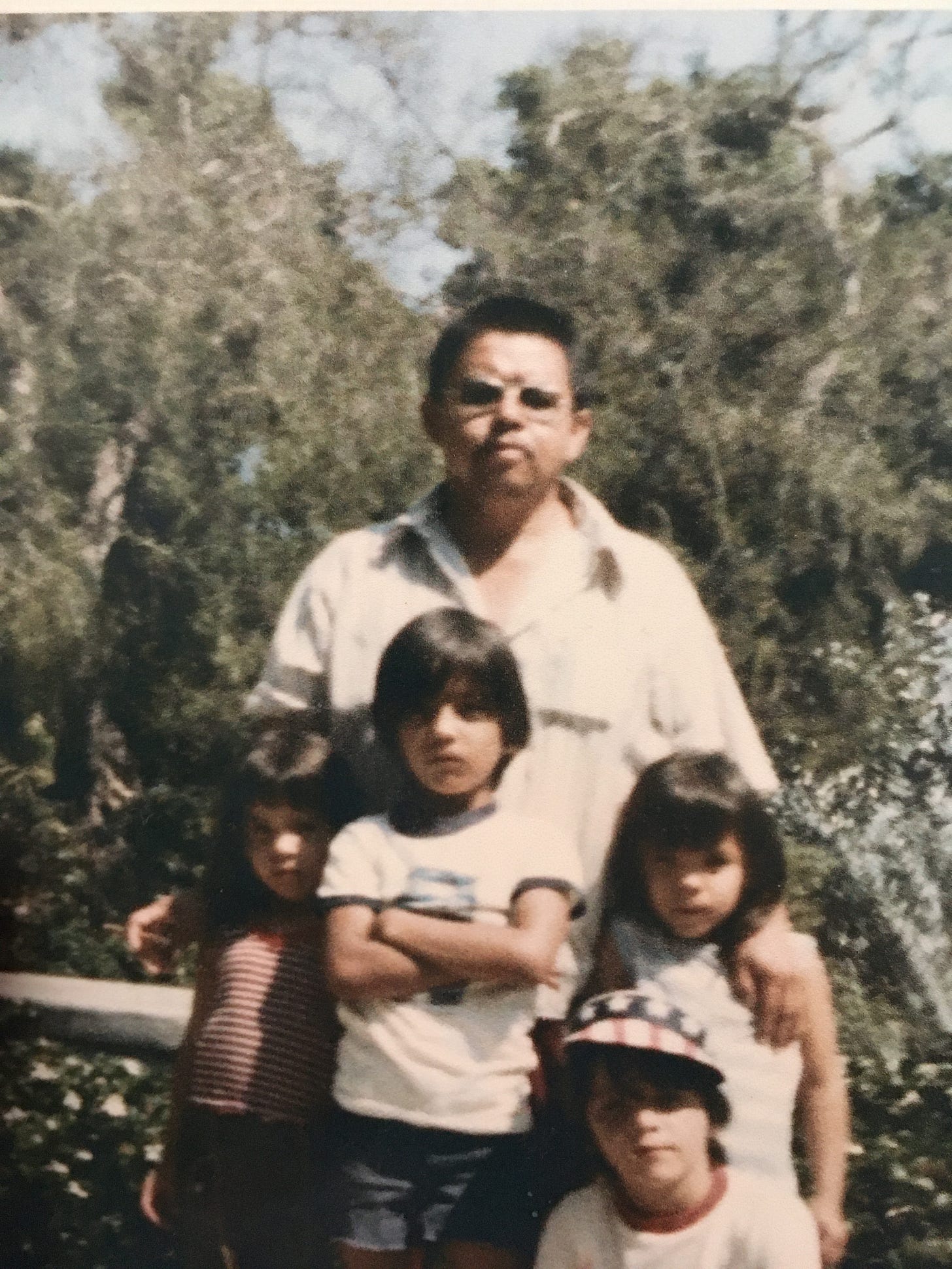

Here’s a photo of my father, siblings, and I.

I’m 100% positive that I was the source of the obvious tension seen in this photo. There’s my father and siblings. Our mother must’ve taken the photo. Look at me with my arms furiously crossed.

Fury could be my Indian name.

I hope this brief and rather narcissistic bio about my early career clarifies that I am unlike approximately 99% of successfully-publishing Native American writers.

In short, I am way fucking Indian and I’ve been on a crazy-ass and decidedly cinematic literary journey.

And I’m telling you this Lana-Turner-with-a-mullet-in-a-soda-shop discovery tale because it does give me a particular expertise.

I’ve published 26 books in my career. Made two movies. Have won major literary awards. Have sold millions of books.

But, despite all that, I’ve always been reluctant to give writing advice. I’m not a good writing teacher because I can’t explicate how I write. I mean—when it comes to the creative process, I can only tell you that shit just arrives in my head.

Shit just arrives in my head and I write it down.

So I’m not here to give you technical advice. I’m here to give you emotional advice.

If you want to sell millions of copies, if you want to win Pulitzers and National Book Awards, if you want to see your book displayed on the front tables in bookstore, if you want attention to be paid, then be prepared to spend long hours, days, months, years, and decades with those fraternal twins named Solitude and Loneliness.

You will write your books alone.

You will rewrite your books alone.

Oh, you might be part of a writing community but that community is the shared space in a Venn diagram. Outside of that space, you will be alone.

If your book is successful then they might send you on a publicity tour. These days, you’ll be an incredibly fortunate author if your press sends you on any kind of publicity tour.

You’ll be alone on that tour.

You’ll be alone in the Lyfts, Ubers, taxis, and town cars,

You’ll be alone in the train and subway stations.

You’ll be alone in the airports.

You’ll be alone eating that goddamn delicious Cinnabon in the airport food court.

You’ll be alone on the airplanes.

You’ll be alone in the rental cars.

You’ll be alone in the hotel lobbies.

You’ll be alone in the hotel rooms.

You’ll be alone when you’re reading from your book in the bookstores.

You’ll be alone in the independent bookstores.

You’ll be alone in the Barnes & Noble.

You’ll be alone when you’re the visiting writer on college campuses.

You’ll be alone when you’re in that precious B&B that your college host mistakenly thought that you’d enjoy because you’re an ARTIST.

You’ll be alone driving from city to city and town to town because you’re afraid of small planes.

You’ll be alone when you do the Google search for your name.

You’ll be terrifyingly alone when you’re scrolling Goodreads.

You’ll be alone at 2 a.m. when you drive through the 24-hour McDonald’s to get a large black coffee to power you for that last hour of travel to that highly-rated and tiny liberal arts college dropped down in a Midwestern cornfield.

You’ll be alone at the college dinners held in your honor. Most of your dinner companions will be gracious. A few will be so intensely jealous that you’ll taste it in your baked chicken.

You’ll be alone at the book conventions. Oh, your publisher, editor, and publicist will be there, too. They will be your business partners first and friends second. And there will be other authors who are friends, colleagues, and acquaintances. But there’s always the shared space in the Venn diagram and the space that you occupy alone.

And, dang, approximately 72% of your fellow authors will be kind but 28% will be pathologically envious and a certain few of them will seek to destroy you through active and passive means.

You might accidentally, stupidly, naively, and self-destructively become friends with one or more of those envious destroyers.

Beware, beware.

Your own ugly jealousy and any addictions and mental and emotional problems that you have will be magnified and make you feel more alone than anything else.

You will be alone with the minibar with its sugar, booze, and salt calling to you.

However…

You will become friends with amazing people.

You will become colleagues with amazing people.

You will meet readers who’ll detail all the ways in which your book has positively changed their lives.

You will meet readers who’ll quote your book back to you.

You will meet other writers who’ll say that they became a writer because of you.

Yes, your book will become the birthplace of other writers.

Your book will be the first day of another writer’s creation story.

You will have the career that every writer dreams of. And it will be horrific. And it will be glorious.

And, day after day, month after month, year after year, you will stare at the blank page and ask yourself, “How the hell am I going to do this again and again? Why do I want to do this again and again?”

You’ll claim to have good answers to existentialist questions.

But you won’t.

You worked with my brother John Luppert at People to People. He speaks fondly of the day you quit to be a brilliant author. Very exciting. He also says all the women in the office were in love with you. Take that faxboy

This post is particularly bitter for women to read because it is incredibly difficult for many of us to find space be alone with our minds. As my yoga teacher, Susan Powter (yes, that one), used to say to us, in a tone of pure fury, "You are going to burn in hell because you just spent 90 minutes doing something that wasn't for your partner, your kids, or your boss." She might have added THINKING about our partners, our kids, or our bosses. It's no coincidence that I didn't start publishing fiction until after my divorce.

My new mantra as an author is going to be, "I will be alone, I will be alone, I will be alone."